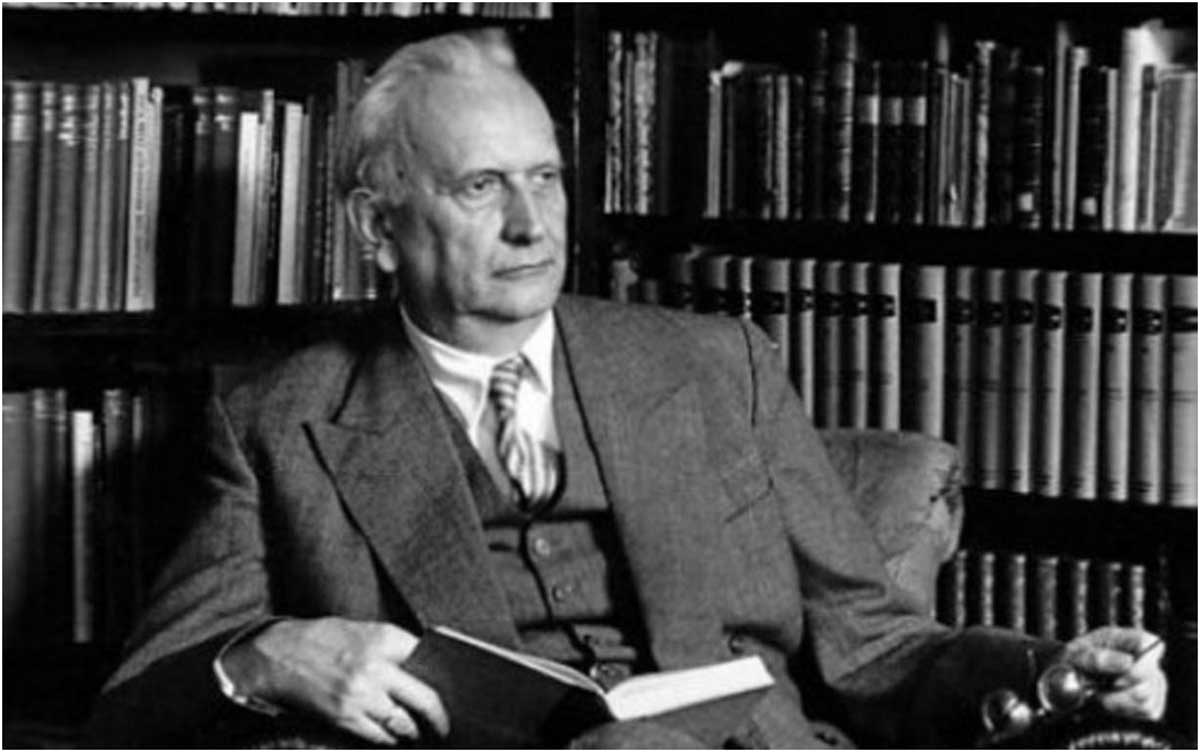

“The enemy is the unphilosophical spirit which knows nothing and wants to know nothing of truth.”

Karl Jaspers, Reason and Anti-Reason in our Time (1971)

By definition, Covid-19 has been a crisis of biology. Nonetheless, certain core explanations for American death and suffering are discoverable outside the boundaries of medicine and pathology. In essence, at least to the extent that these tangible costs express America’s deeply-rooted antipathy to various considerations of intellect – to what twentieth century philosopher Karl Jaspers would call a “spirit which knows nothing and wants to know nothing of truth” – we have also been enduring a crisis of philosophy.

This is not an easy argument to make in the United States. “Philosophy” is a tough term to embrace for an American audience. Prima facie, it is “elitist.” At a minimum, it is (allegedly) impractical, contrived and “highfalutin.” In this country, after all, even the most casual mention of “intellect” or “intellectual” will normally elicit cries of disapproval or howls of execration.

No “real” American, we have been instructed from the start, should ever be focused on such a needlessly arcane subject matter or pretentiously elevated discourse.

Big words be damned. Plainly, this a nation of impressively tangible accomplishments, of conspicuous “greatness” and “common sense.” Who needs abstract and disciplined learning, especially when so many philosophers were themselves never “real Americans”?

Still, truth is exculpatory and any proper answer ought to be prompt, unhesitant and unambiguous. Accordingly, there are times for every nation when history, science and intellect deserve an absolute pride of place. Recalling Plato’s parable of the cave in The Republic, our politics are always just reflection, merely a misleading “shadow” of reality, merely epiphenomenal.

In the United States, as anywhere else that has built carefully upon millennia of dialectical education, politics can offer only a deformed reflection of what lies more meaningfully below. It is largely because of our collective unwillingness to recognize this telling relationship, and not just a virulent virus per se, that we Americans have now suffered substantially more than a half million pandemic fatalities.

This lethal unwillingness represents a self-evident result of American anti-intellectualism. Though unverifiable by science-based standards, it also reveals a palpable vacancy of “soul.”[1] Sometimes, such less tangible or “soft” problems still warrant very close attention.

This is one of those times.

There also remains more to consider. Donald J. Trump is gone, but the crudely retrograde and “common sense” sentiments that first brought him to power endure unabated. Generally lacking the refined intellectual commitments of mind, We the people should not express undue surprise or incredulity at the sheer breadth of our collective failures. Over too many years, the always- seductive requirements of wealth and “success” were casually allowed to become the highest ideal of American life. Among other things, these vaunted requirements turned out to be very high-cost delusions.

Too-many American debilities remain rooted in “common sense.” Over the years, American well-being and “democracy” have allegedly sprung from an orchestrated posture of engineered consumption. In this steeply confused derivation, our national marching instructions have remained clear and shameless: “You are what you buy.” It follows from such shameless misdirection that the country’s ever-growing political scandals and failures were the altogether predictable product of a society where anti-intellectual and unheroic lives are actively encouraged. Even more insidiously, American success is measured not by any rational criteria of mind, compassion and “soul,” but dolefully, mechanically, absent commendable purpose and without any “collective will.”[2]

There is more. What most meaningfully animates American politics today is not a normally valid interest in progress or survival, but a steadily-escalating fear of personal defeat or private insignificance. Though sometimes most readily apparent at the presidential level, singly, such insignificance can also be experienced collectively, by an entire nation. Either way, its precise locus of origin concerns certain deeply-felt human anxieties about not being valued, about not “belonging,”[3] about not being “wanted at all.”[4]

For any long-term national renaissance to become serious, an unblemished candor must first be allowed to prevail. Perpetually ground down by the demeaning babble of half-educated pundits and jabbering politicos, We the people are only rarely motivated by elements of real insight or courage. To wit, we are just now learning to understand that our badly injured Constitution was subjected to variously dissembling increments of abrogation, assaults by an impaired head of state who “loved the poorly educated,”[5] who proudly read nothing, and who yearned not to serve his country,[6] but only to be gratifyingly served by its endlessly manipulated citizens.

Openly, incontestably, Donald J. Trump abhorred any challenging considerations of law, intellect or independent thought. For the United States, it became a literally lethal and unforgivable combination. At the chaotic end of his self-serving tenure, Trump’s personal defeat was closely paralleled by near-defeat of the entire nation. Lest anyone forget, the catastrophic events at the Capitol on January 6, 2021 were designed to undermine or overthrow the rule of Constitutional order in the United States.

Nothing less.

There is more. To understand the coinciding horrors of the Corona virus and Trump presidency declensions, we must first look more soberly beyond mere “reflections,” beyond transient personalities and the daily news. Even now, in these United States, a willing-to-think individual is little more than a quaint artifact of some previously-lived or imagined history. At present, more refractory than ever to courage, intellect and learning, our American “mass” displays no decipherable intentions of taking itself more seriously.[7]

None at all.

“Headpieces filled with straw…” is the way poet T S Eliot would have characterized present-day American society. He would have observed, further, an embittered American “mass” or “herd” marching insistently backward, cheerlessly, wittingly incoherent and in potentially pitiful lockstep toward future bouts of lethal epidemic illness. About any corollary unhappiness, let us again be candid.

It is never a happy society that chooses to drown itself in limitless mountains of drugs and vast oceans of alcohol.

What’s next for the still-imperiled Republic? Whatever our specific political leanings or party loyalties, We the people have at least restored a non-criminal resident to the American White House.[8] At the same time, our self-battering country still imposes upon its exhausted people the hideously breathless rhythm of a vast and uncaring machine.Before Cocvid-19, we witnessed, each and every day, an endless line of trains, planes and automobiles transporting weary Americans to yet another robotic workday, a day too-often bereft of any pleasure or reward or of hope itself. Now there is good reason for greater day-to-day political hope, and for this we should be grateful.

But there is still no American “master plan” for a suitably transformed national consciousness.

“I think therefore I am,” announces Descartes, but what exactly do I think?”

Answers come quickly top mind. Even now, We the people lack any unifying sources of national cohesion except for celebrity sex scandals, local sports team loyalties, inane conspiracy theories and the comforting but murderous brotherhoods of war.[9] As for the more than seven million people stacked cheek to jowl in our medieval prisons, two-thirds of those released will return to crime and mayhem. Simultaneously, the most senior and recognizable white collar criminals – in part, those Trump-era sycophants who managed to effortlessly transform personal cowardice into a religion – can look forward to lucrative book contracts. These agreements are for manuscripts that they themselves are intellectually unfit to write.

We Americans inhabit the one society that could have been different. Once we displayed a unique potential to nurture individuals to become more than just a “mass,” “herd” or “crowd.”[10] Then, Ralph Waldo Emerson had described us as a people animated by industry and self-reliance, not by moral paralysis, fear and trembling. Friedrich Nietzsche would have urged Americans to “learn to live upon mountains” (that is, to becomewillfully thinking individuals), but today an entire nation remains grudgingly content with the very tiniest of elevations.

In Zarathustra, Nietzsche warned decent civilizations never to seek the “higher man”[11] at the “marketplace,” but that is where America first discovered Donald J. Trump.

What could have gone wrong? Trump was, after all, very rich. How then could he possibly not be smart and virtuous? Perhaps, as Reb Tevye remarks famously in Fiddler on the Roof, “If you’re rich they think you really know.”

There is more. Many could never really understand Vladimir Lenin’s concept of a “useful idiot,” or the recently-pertinent corollary that an American president could become the witting marionette of his Russian counterpart. But, again, truth is exculpatory. The grievously sordid derelictions we Americans were forced to witness at the end of the Trump presidency resembled The Manchurian Candidate on steroids.

And in what was perhaps the most exquisite irony of this destructive presidency, the very same people who stood so enthusiastically behind their man in the White House had themselves been raised with the fearful idea of a protracted Cold War and ubiquitous “Russian enemy.”

“Credo quia absurdum,” said the ancient philosopher Tertullian. “I believe because it is absurd.”

The true enemy currently faced by the United States is not any one individual person or ideology, not one political party or another. It is rather We the People. As we may learn further from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: “The worst enemy you can encounter will always be you, yourself; you will lie in wait for yourself in caves and woods.” And so we remain, even today, poised fixedly against ourselves and against our survival, battered by an unprecedented biological crisis nurtured by the former US president’s unforgivable policy forfeitures.

Bottom line? In spite of our proudly clichéd claim to “rugged individualism,” we Americans are shaped not by any exceptional capacity but by harshly commanding patterns of cowardly conformance. Busily amusing ourselves to death with patently illiterate and cheap entertainments, our endangered American society fairly bristles with annoying jingles, insistent hucksterism, crass allusions and telltale equivocations. Surely, we ought finally to inquire: Isn’t there more to this long-suffering country than abjured learning, endless imitation and an expansively manipulating commerce? Whatever we might choose to answer, the available options are increasingly limited.

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” observed the Transcendentalist poet Walt Whitman, but now, generally, the self-deluding American Selfis created by stupefying kinds of “education,”[12] by far-reaching patterns of tastelessness and by a pervasive national culture of unceasing rancor and gratuitous obscenity.

There are special difficulties. Only a rare “few” can ever redeem courage and intellect in America,[13] but these quiet souls usually remain well hidden, even from themselves. One will never discover them engaged in frenetic and agitated self-advertisement on television or online. Our necessary redemption as a people and aa a nation can never be generated from among the mass, herd or crowd. There is a correct way to fix our fractionating country, but not while We the people insistently inhabit various pre-packaged ideologies of anti-thought and anti-Reason, that is, by rote, without “mind” and without integrity.[14]

Going forward, inter alia, we must finally insist upon expanding the sovereignty of a newly courageous and newly virtuous[15] citizenry. In this immense task, very basic changes will first be needed at the level of microcosm, the level of the individual human person. Following the German Romantic poet Novalis’ idea that to become a human being is essentially an art (“Mensch werden ist eine Kinst“), the Swiss-German author/philosopher Hermann Hesse reminds us that every society is a cumulative expression of utterly unique individuals. In this same regard, Swiss psychologist Carl G. Jung goes even further, claiming, in The Undiscovered Self (1957), that every society represents “the sum total of individual souls seeking redemption.”[16]

One again, as in our earlier references to Sigmund Freud, the inherently “soft” variable of “soul” is suitably acknowledged.

Looking to history and logic, it would be very easy to conclude that the monumental task of intellectual and moral reconstruction lies well beyond our normal American capacities. Nonetheless, to accede to such a relentlessly fatalistic conclusion would be tantamount to irremediable collective surrender. This could be unconscionable. Far better that the citizens of a sorely imperiled United States grasp for any still-residual sources of national and international unity, and exploit this universal font for both national and international survival.

We have been considering the effects of an “unphilosophical spirit which knows nothing and wants to know nothing of truth.”[17] During the past several years, huge and conspicuous efforts have been mounted to question the “cost-effectiveness” of an American college education. These often-shallow efforts ignore that the core value of a university degree lies not in its projected purchasing power, but in disciplined learning for its own sake. When young people are asked to calculate the value of such a degree in solely commercial terms, which is the case today, they are being asked to ignore both the special pleasures of a serious education (e.g., literature, history, art, music, philosophy, etc.) and the cumulative benefits of genuine learning to a mature and viable democracy.

These commerce-based requests are shortsighted. Had these benefits been widely understood long before the 2016 presidential election, the United States might never have had to endure the multiplying horrors of Covid-19 and of variously still-heightened risks of a nuclear war. Only by understanding this underlying point about learning and education could Americans ever correctly claim that they have learned what is most important from the pandemic.

On its face, such a claim would have potentially existential import. Wanting to partake of authentic truth rather than reflections or shadows, it ought never be minimized or disregarded. At some stage, the costs of any such forfeited understanding could be immeasurable.

[1] Freud was always darkly pessimistic about the United States, which he felt was “lacking in soul” and a place of great psychological misery or “wretchedness.” In a letter to Ernest Jones, Freud declared unambiguously: “America is gigantic, but it is a gigantic mistake.” (See: Bruno Bettelheim, Freud and Man’s Soul (1983), p. 79.

[2] The origin of this term in modern philosophy lies in the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer, especially The World as Will and Idea (1818). For his own inspiration (and by his own expressed acknowledgment), Schopenhauer drew freely upon Goethe. Later, Nietzsche drew just as freely (and perhaps still more importantly) upon Schopenhauer. Goethe also served as a core intellectual source for Spanish existentialist Jose Ortega y’ Gasset, author of the prophetic work, The Revolt of the Masses (Le Rebelion de las Masas (1930). See, accordingly, Ortega’s very grand essay, “In Search of Goethe from Within” (1932), written for Die Neue Rundschau of Berlin on the occasion of the centenerary of Goethe’s death. It is reprinted in Ortega’s anthology, The Dehumanization of Art (1948) and is available from Princeton University Press (1968).

[3]The extent to which some young Americans are willing to go to “belong” can be illustrated by certain recent incidents of college students drinking themselves to death as part of a fraternity hazing ritual. Can there be anything more genuinely pathetic than a young person who would accept virtually any such measure of personal debasement and risk in order to “fit in”?

[4] “It is getting late; shall we ever be asked for?” inquires the poet W H Auden in The Age of Reason. “Are we simply not wanted at all?”

[5] Said candidate Donald Trump in 2016, “I love the poorly educated.” This strange statement appears to echo Third Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels at Nuremberg rally in 1935: “Intellect rots the brain.”

[6] This brings to mind the timeless observation by Creon, King of Thebes, in Sophocles’ Antigone: “I hold despicable, and always have anyone who puts his own popularity before his country.”

[7] “The mass-man,” we may learn from Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y’ Gasset (The Revolt of the Masses, 1930), “has no attention to spare for reasoning; he learns only in his own flesh.”

[8] In this connection, cautions Sigmund Freud: “Fools, visionaries, sufferers from delusions, neurotics and lunatics have played great roles at all times in the history of mankind, and not merely when the accident of birth had bequeathed them sovereignty. Usually, they have wreaked havoc.”

[9] War, of course, is arguably the most worrisome consequence of an anti-intellectual and anti-courage American presidency. For the moment, largely as a result of the intellectually dissembling Trump presidency, the most plausible geographic area of concern would be a nuclear war with North Korea. https://mwi.usma.edu/theres-no-historical-guide-assessing-risks-us-north-korea-nuclear-war/

[10] “The crowd,” said Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, “is untruth.” Here, the term “crowd” is roughly comparable to C.G. Jung’s “mass,” Friedrich Nietzsche’s “herd” and Sigmund Freud’s “horde.”

[11]We can reasonably forgive the apparent sexism of this term, both because of the era in which it was offered and because the seminal European philosopher meant this term to extend to both genders.

[12] In an additional irony, these already unsatisfactory kinds of education will be supplanted by even more intrinsically worthless forms of learning. Most notable, in this regard, is the almost wholesale shift to online education, a shift made more necessary and widespread by the Covid-19 disease pandemic, but unsatisfactory nonetheless.

[13] The term is drawn here from the Spanish existential Jose Ortega y’ Gasset, especially his classic The Revolt of the Masses (1930).

[14] “There is no longer a virtuous nation,” warns the poet William Butler Yeats, “and the best of us live by candlelight.”

[15] As used by ancient Greek philosopher Plato, the term “virtuous” includes elements of wisdom and knowledge as well as morality.

[16] Carl G. Jung eagerly embraced the term “soul” following preferences of Sigmund Freud, his one-time mentor and colleague. Also, says Jung in The Undiscovered Self (1957): “The mass crushes out the insight and reflection that are still possible with the individual, and this necessarily leads to doctrinaire and authoritarian tyranny if ever the constitutional State should succumb to a fit of weakness.”

[17]Although this present consideration has been offered as a pièce d’occasion, it also has much wider conceptual applications and implications.