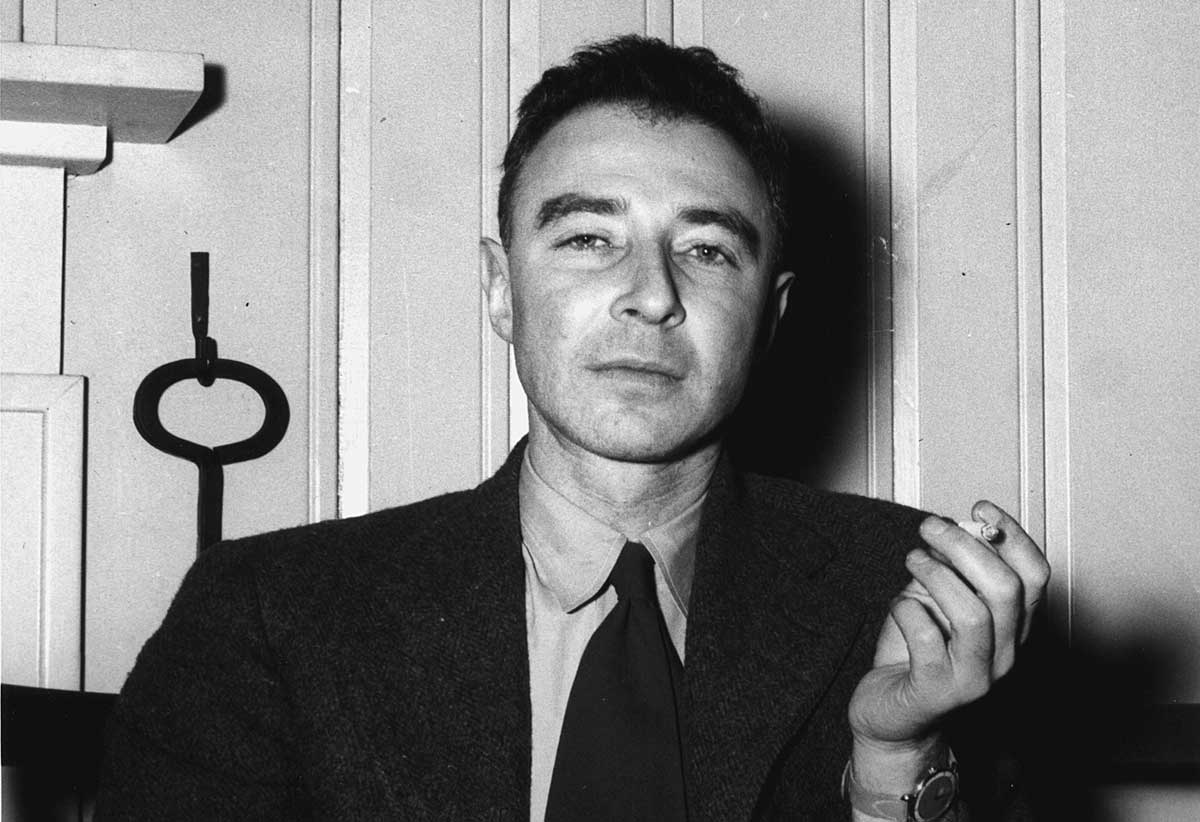

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” -J. Robert Oppenheimer citing to Bahgavad Gita at first atomic test on July 16, 1945

A first thought dawns. Nuclear weapons are unique in the history of warfare. Even a single instance of nuclear warfighting would signify unprecedented and irremediable failure. In essence, nuclear weapons can succeed only though non-use.[1] The most obvious example of such a more-or-less plausible “success” would be system-wide and stable conditions of nuclear deterrence.

There are many relevant details, both military and legal. Not all nuclear wars would have the same conceptual origin. Should nuclear deterrence fail, a core distinction would concern variously probabilistic differences between deliberate or intentional nuclear war and a nuclear war that would be unintentional or inadvertent. In all cases, this would represent an especially vital distinction.[2]

Should nuclear deterrence fail, it could be on account of antecedent arms control failures or shortcomings and assorted misunderstandings or decisional miscalculations. Here, inherently complex intersections between strategy and law could prove determinative. Though durable foundations of nuclear war avoidance should always include comprehensive elements of treaty-based nuclear arms control, no such inclusion could ever be adequate.

Regarding interrelated strategic elements of nuclear war avoidance, there will be multi-layered problems for science-based calculation. In this connection, because there has never been an authentic nuclear war(Hiroshima and Nagasaki don’t “count”),[3] determining relevant probabilities would be literally impossible. To clarify, in logic and mathematics, true probabilities must always derive from the determinable frequency of pertinent past events. Ipso facto, when there are no such past events, nothing could be determined with any predictive reliability.

Still, impediments notwithstanding, intellect-directed analysts will have to devise optimal strategies for averting nuclear war.[4] Such indispensable calculations will vary, among other things, according to (1) presumed enemy intention; (2) presumed plausibility of accident or hacking intrusion; and/or (3) presumed likelihood of decisional miscalculation. When considered together as cumulative categories of nuclear war threat, all three component risks of an unintentional nuclear war would be “inadvertent.”Any particular case of an accidental nuclear war would be inadvertent, but not every case of inadvertent nuclear war would be the result of an accident.

All listed examples represent potentially intersecting elements of nuclear war avoidance. This bewildering problem should never be approached by American national security policy-makers or by the US president as a narrowly political or tactical issue. Rather, informed by in-depth historical understanding and by carefully refined analytic capacities, US military planners should prepare to deal with a large variety of overlapping explanatory factors/norms, including jurisprudential[5] or legal ones.[6]

There is more. At times, studied intersections under could be determinably synergistic. At such intellect-challenging times, the “whole” of any injurious effect would be greater than the sum of its “parts. Going forward, focused attention on pertinent synergies should remain a primary analytic objective.[7]

In dealing with certain still-growing nuclear war risks involving North Korea, Ukraine, Russia or Iran, no single concept could prove more important than synergy.[8] Unless such interactions are reliably and correctly evaluated, an American president could sometime sorely underestimate the total impact of any considered nuclear engagement. The manifestly tangible flesh and blood consequences of any such underestimations would likely be very high. They could defy both analytic imaginations and any post-war legal justifications.

Looking ahead, in any complex strategic risk assessments regarding adversarial military nuclear intentions, the concept ofsynergy should be assigned appropriate pride of place.[9] The only conceivable argument for an American president willfully choosing to ignore the effects of synergy would be that the associated US defense policy considerations appear “too complex.” When fundamental US national security issues are at stake, however, any such viscerally dismissive argument would be unacceptable.

For the present writer, such reasoning has long represented familiar intellectual terrain. In brief, I have been publishing about difficult and related strategic-legal issues for more than fifty years. After four years of doctoral study at Princeton in the late 1960s, historically a prominent center of American nuclear strategic thought (recall especially Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer), I began to consider adding a modest personal contribution to a then-evolving nuclear literature. By the late 1970s, I was cautiously preparing a new manuscript on US nuclear strategy,[10] and, by variously disciplined processes of correct inference, on the corresponding risks of a nuclear war.[11]

At that early stage of an emerging discipline, I was most interested in US presidential authority to order the use of American nuclear weapons.

Almost immediately, after spending time at SAC (Strategic Air Command) headquarters,[12] I learned that allegedly reliable safeguards had been incorporated into all operational nuclear command/control decisions, but also that these same safeguards could not be applied at the presidential level. To a young scholar searching optimistically for meaningful nuclear war avoidance opportunities, this ironic disjunction didn’t make any sense. So, what next?

It was a time for gathering suitable clarifications. I reached out to retired General Maxwell D. Taylor, a former Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. In reassuringly rapid response to my query, General Taylor sent a comprehensive handwritten reply. Dated 14 March 1976, the distinguished General’s detailed letter concluded ominously: “As to those dangers arising from an irrational American president, the only protection is not to elect one.”[13]

Until recently, I had never given any extended thought to this authoritative response. Today, following the incoherent presidency of Donald J. Trump (and the possible coming of Trump II in 2024) General Taylor’s 1976 warning takes on more urgent meanings. Based on variously ascertainable facts and extrapolations (called “entailments” in formal philosophy of science terminology) rather than wishful thinking, we ought now to assume that if Donald J. Trump were to return to the White House and exhibit accessible signs of emotional instability, irrationality or delusional behavior, he could still order the use of American nuclear weapons. He could do this officially, legally[14] and without compelling expectations of any nuclear chain-of-command “disobedience.”[15]

Still more worrisome, any US president could become emotionally unstable, irrational or delusional, but not exhibit such grave liabilities conspicuously.

What then?

A corollary question should quickly come to mind:

What precise stance should be assumed by the National Command Authority (Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and several others) if it should ever decide to oppose an “inappropriate” presidential order to launch American nuclear weapons?

Could the National Command Authority (NCA) “save the day,” informally, by acting in an impromptu or creatively ad hoc fashion? Or should refined preparatory steps already have been taken in advance, “preemptively”? That is, should there already be in place certain credible and effective statutory measures to (1) assess the ordering president’s reason and judgment; and (2) countermand any inappropriate or wrongful nuclear order?

Presumptively, in US law, Article 1 (Congressional) war-declaring expectations of the Constitution aside, any presidential order to use nuclear weapons, whether issued by an apparently irrational president or by an otherwise incapacitated one, would have to be obeyed. To do otherwise in such circumstances would be illegal on its face. Any chain-of-command disobedience would be impermissible prima facie.[16]

There is more. In principle, at least, any US president could order the first use of American nuclear weapons even if this country were not under a nuclear attack. Further strategic and legal distinctions would need to be made between a nuclear “first use” and a nuclear “first strike.” These would not be minor distinctions.[17]

While there exists an elementary yet substantive difference between these two options, it is an operational distinction that candidate Donald Trump failed to understand during the 2016 presidential campaign debates. As this former and now re-aspiring president reads nothing about such weighty matters – literally nothing at all – there remains good reason for task-appropriate US nuclear policy refinements.

What next? Where exactly should the American polity and government go from here on these overriding national security decision-making issues?[18] To begin, a coherent and comprehensive answer will need to be prepared for the following basic question:

If faced with any presidential order to use nuclear weapons, and not offered sufficiently appropriate corroborative evidence of any actually impending existential threat, would the National Command Authority be: (1) be willing to disobey, and (2) be capable of enforcing such needed expressions of disobedience?

In any such unprecedented crisis-decision circumstances, all authoritative judgments could have to be made in a compressively time-urgent matter of minutes, not of hours or days. As far as any useful policy guidance from the past might be concerned, there could exist no scientifically valid way to assess the true probabilities of possible outcomes. This is because all scientific judgments of probability – whatever the salient issue or subject – must be based upon recognizably pertinent past events.

On matters of a nuclear war, there are no pertinent past events. This is a fortunate absence, of course, but one that would still stand in the way of rendering reliable decision-making predictions. The dangerous irony here should be obvious.

Whatever the determinable scientific obstacles, the optimal time to prepare for any such vital US national security difficulties is now. Once we were already embroiled in extremis atomicum, it would be too late.

Regarding the specific problem areas of an already nuclear North Korea and a nearly-nuclear Iran, an American president will need to avoid any seat-of-the-pants calculations. For example, faced with dramatic uncertainties about counterpart Kim Jung Un’s expected willingness to push the escalatory envelope, an American president could suddenly and unexpectedly find himself faced with a fearfully stark choice between outright capitulation and nuclear war. For even an intellectually gifted US president (hardly a plausible present-day expectation), any such choice could be “paralyzing.”

To avoid being placed in such a limited choice strategic environment, a US president should understand that having a larger national nuclear force might not bestow any critical bargaining or crisis-outcome advantages. On the contrary, this seeming advantage could generate unwarranted US presidential overconfidence and/or various resultant forms of decisional miscalculation. In any such wholly unfamiliar, many-sided and unprecedented matters, arsenal size could actually matter, but perhaps counter-intuitively, inversely, or in various ways not yet fully understood.

More than likely, any prosaic analogies would be misconceived. Nuclear war avoidance is not a matter resembling commercial marketplace negotiations.[19] While the search for some sort of “escalation dominance” (successful competition in risk-taking) may be common to many sorts of commercial deal-making, the cumulative costs of any related nuclear security policy losses would always be sui generis or one-of-a-kind.

There is more. In certain fragile matters of world politics, even an inadvertent decisional outcome could include a nuclear war. Here, whether occasioned by accident, hacking or “mere” miscalculation, there could be no meaningful “winner.” At a conceptual level, any US president ought to understand this as an elementary sort of understanding.

In the paroxysmal aftermath of any unintended nuclear conflict, those authoritative American decision-makers who had once accepted former President Donald J. Trump’s oft-stated preference for “attitude” over “preparation” would likely reconsider their earlier error. By then, however, it would be too late. As survivors of a once-preventable nuclear conflagration, now-stunned officials might only envy the dead. This is the case, moreover, whether the nuclear conflict had been intentional or unintentional, and whether it had been occasioned by base motives, miscalculation, computer error, hacking intrusion or by weapon-system/infrastructure accident.

Today, more than 78 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear war remains an incurable “disease.” To ensure credible deterrence, a US president would no longer need to respond to a nuclear attack immediately. Because the triad of strategic weaponry includes cumulatively invulnerable submarine forces, this country no longer needs to rely upon a destabilizing “launch on warning” nuclear posture. This means, among other things, that a president of the United States need no longer be granted sole decisional authority over America’s nuclear weapons.

Any continuing failure of United States law and practice to acknowledge this sobering transformation could lead to an adversarial use of nuclear weapons – by this country, by its then-evident adversary, or by both. In any such scenario, the atomic conflagration would almost certainly dwarf the 1945 effects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It follows, above all else, that nuclear war avoidance is mandated by the conjunction of human survival and human reason.[20]

Physicist and Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer, subject of the film released in July 2023, clung fixedly to the hope that nuclear weapons could become peace-maximizing rather than destabilizing. In a lecture delivered before the George Westinghouse Centennial Forum on May 16, 1946, the celebrated physicist commented: “The development of nuclear weapons can make, if wisely handled, the problem of preventing war not more hopeless, but more hopeful than it would otherwise have been….” Back in 1946, Oppenheimer did not anticipate a broad variety of troublesome issues, including the proliferation of nuclear weapons (“vertical” and “horizontal”) to states and sub states; risks of an unintentional nuclear war; failure of law-based nuclear arms control; and the inextinguishable irrationality of human decision-makers seeking “escalation dominance” in the midst of chaotic crises.

Today, looking toward a grievously uncertain national and global future, the only rational course for humankind is to collectively eschew nuclear warfighting as a prospective benefit, and to do whatever is necessary in law and strategy to build more durable foundations of nuclear war avoidance. For the most part, this challenging task must be intellectual rather than political.[21] Moreover, to meet this unique task, nuclear war avoidance can never be accomplished in the explosive context of belligerent nationalism and global chaos. Among other things, this requires the will[22] to acknowledge that entire civilizations can have the same mortality as an individual human being, and that the nuclear weapon states themselves can “become death.”

[1] Says Sun-Tzu in The Art of War: “Subjugating the enemy’s army without fighting is the true pinnacle of excellence. (Chapter 3, “Planning Offensives”).

[2] For authoritative early accounts by this author of nuclear war effects, see: Louis René Beres, Apocalypse: Nuclear Catastrophe in World Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); Louis René Beres, Mimicking Sisyphus: America’s Countervailing Nuclear Strategy (Lexington, Mass., Lexington Books, 1983); Louis René Beres, Reason and Realpolitik: U.S. Foreign Policy and World Order (Lexington, Mass., Lexington Books, 1984); and Louis René Beres, Security or Armageddon: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy (Lexington, Mass., Lexington Books, 1986). Most recently, by Professor Beres, see: Surviving Amid Chaos: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy (New York, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016; 2nd ed. 2018).

[3] The atomic attacks on Japan in August 1945 represented nuclear weapons use in a conventional war.

[4] Reminds Guillaume Apollinaire, “It must not be forgotten that it is perhaps more dangerous for a nation to allow itself to be conquered intellectually than by arms.” (The New Spirit and the Poets (1917)

[5] For the authoritative sources of international law, see art. 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice: STATUTE OF THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE, Done at San Francisco, June 26, 1945. Entered into force, Oct. 24, 1945; for the United States, Oct. 24, 1945. 59 Stat. 1031, T.S. No. 993, 3 Bevans 1153, 1976 Y.B.U.N., 1052.

[6] Regarding these pertinent considerations of law, issues of personal criminal responsibility must be ones of high importance. Significantly, criminal responsibility of leaders under international law is not limited to direct personal action or limited by official position. On this peremptory principle of “command responsibility,” or respondeat superior, see: In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. 1 (1945); The High Command Case (The Trial of Wilhelm von Leeb), 12 Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals 1 (United Nations War Crimes Commission Comp., 1949); see Parks, Command Responsibility For War Crimes, 62 MIL.L. REV. 1 (1973); O’Brien, The Law Of War, Command Responsibility And Vietnam, 60 GEO. L.J. 605 (1972); U.S. Dept. Of The Army, Army Subject Schedule No. 27 – 1 (Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Hague Convention No. IV of 1907), 10 (1970). The direct individual responsibility of leaders is also unambiguous in view of the London Agreement, which denies defendants the protection of the act of state defense. See AGREEMENT FOR THE PROSECUTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE MAJOR WAR CRIMINALS OF THE EUROPEAN AXIS, Aug. 8, 1945, 59 Stat. 1544, E.A.S. No. 472, 82 U.N.T.S. 279, art. 7.

[7] Such focus on synergies could shed a parallel light upon the entire world system’s state of disorder (a view that would reflect what the physicists prefer to call “entropic” conditions), and could themselves be more-or-less dependent upon a pertinent American president’s subjective metaphysics of time. For an early article by this author dealing with linkages between such a subjective metaphysics and national crisis decision-making, see: Louis René Beres, “Time, Consciousness and Decision-Making in Theories of International Relations,” The Journal of Value Inquiry, Vol. VIII, No.3., Fall 1974, pp. 175-186.

[8] Prospective problems stemming from synergy also bring to mind the Clausewitzian concept of “friction,” a concept that is not the same as synergy, but that also emphasizes the always-key elements of interaction and unpredictability. See Carl von Clausewitz, On War, especially Chapter VI, “Friction in War.”

[9] See earlier, by this author, at Harvard National Security Journal (Harvard Law School): Louis René Beres, https://harvardnsj.org/2015/06/core-synergies-in-israels-strategic-planning-when-the-adversarial-whole-is-greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts/

[10] Earlier, by this author, see: Louis René Beres, The Management of World Power: A Theoretical Analysis (University of Denver, 1973) and Louis René Beres, Transforming World Politics: The National Roots of World Peace (University of Denver, 1975).

[11] This book was subsequently published in 1980 by the University of Chicago Press: Louis René Beres, Apocalypse: Nuclear Catastrophe in World Politics. http://www.amazon.com/Apocalypse-Nuclear-Catastrophe-World-Politics/dp/0226043606

[12] Years later, I became a frequent co-author with General (USAF/ret.) John T. Chain, previously Commander-in-Chief, US Strategic Air Command (CINCSAC).

[13] Expressions of decisional irrationality could take different or overlapping forms. These include a disorderly or inconsistent value system; computational errors in calculation; an incapacity to communicate efficiently; random or haphazard influences in the making or transmittal of particular decisions; and the internal dissonance generated by any structure of collective decision-making (i.e., assemblies of pertinent individuals who lack identical value systems and/or whose organizational arrangements impact their willing capacity to act as a single or unitary national decision maker).

[14] Here, meaningful considerations of law would be more-or-less bifurcated between domestic or municipal law and international law. Still, international law is part of United States jurisprudence. In the words of Mr. Justice Gray, delivering the judgment of the US Supreme Court in Paquete Habana (1900): “International law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction….” (175 U.S. 677(1900)) See also: Opinion in Tel-Oren vs. Libyan Arab Republic (726 F. 2d 774 (1984)).Moreover, the specific incorporation of treaty law into US municipal law is expressly codified at Art. 6 of the US Constitution, the so-called “Supremacy Clause.”

[15] Still, there could remain certain authoritative considerations of international law, specifically those having to do with strategies of preemption or “anticipatory self-defense.” Such considerations can be found not in conventional law (art. 51 of the UN Charter supports only post-attack expressions of individual or collective self-defense), but rather in customary international law. The precise origins of anticipatory self-defense in such customary law lie in the Caroline, a case that concerned the unsuccessful rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada against British rule. Following this case, the serious threat of armed attack has generally justified certain militarily defensive actions. In an exchange of diplomatic notes between the governments of the United States and Great Britain, then U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster outlined a framework for self-defense that did not require an antecedent attack. Here, the jurisprudential framework permitted a military response to a threat so long as the danger posed was “instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.” See: Beth M. Polebaum, “National Self-defense in International Law: An Emerging Standard for a Nuclear Age,” 59 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 187, 190-91 (1984) (noting that the Caroline case had transformed the right of self-defense from an excuse for armed intervention into a legal doctrine). Still earlier, see: Hugo Grotius, Of the Causes of War, and First of Self-Defense, and Defense of Our Property, reprinted in 2 Classics of International Law, 168-75 (Carnegie Endowment Trust, 1925) (1625); and Emmerich de Vattel, The Right of Self-Protection and the Effects of the Sovereignty and Independence of Nations, reprinted in 3 Classics of International Law, 130 (Carnegie Endowment Trust, 1916) (1758). Also, Samuel Pufendorf, The Two Books on the Duty of Man and Citizen According to Natural Law, 32 (Frank Gardner Moore., tr., 1927 (1682).

[16] Nonetheless, there could arise various contrary expectations of international law, including certain “peremptory” norms that concern both the right to use international force and/or the amount or type of force that may correctly be applied. According to Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties: “…a peremptory norm of general international law is a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of states as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character.” See: Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Done at Vienna, May 23, 1969. Entered into force, Jan. 27, 1980. U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 39/27 at 289 (1969), 1155 U.N.T.S. 331, reprinted in 8 I.L.M. 679 (1969).

[17] Also, under authoritative terms of international law, there would be coinciding concerns about the egregious crime of “aggression.” See especially: RESOLUTION ON THE DEFINITION OF AGGRESSION, Dec. 14, 1974, U.N.G.A. Res. 3314 (XXIX), 29 U.N. GAOR, Supp. (No. 31) 142, U.N. Doc. A/9631, 1975, reprinted in 13 I.L.M. 710, 1974; and CHARTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS, Art. 51. Done at San Francisco, June 26, 1945. Entered into force for the United States, Oct. 24, 1945, 59 Stat. 1031, T.S. No. 993, Bevans 1153, 1976, Y.B.U.N. 1043.

[18] Also worth bearing in mind here are the different ways in which the United States can permissibly adapt international law to these issues. Apropos of this corresponding query, international law remains a “vigilante” or “Westphalian” system of jurisprudence. The Peace of Westphalia created the still-existing decentralized or self-help state system. See: Treaty of Peace of Munster, Oct. 1648, 1 Consol. T.S. 271; and Treaty of Peace of Osnabruck, Oct. 1648, 1, Consol. T.S. 119, Together, these two treaties comprise the Peace of Westphalia.

[19] Here we may recall Nietzsche’s philosophic warning in Zarathustra: “Do not seek the higher man at the marketplace.”

[20]The specific importance of reason to legal judgment was prefigured in ancient Israel, which accommodated reason within its core system of revealed law. Jewish theory of law, insofar as it displays the marks of natural law, offers a transcending order revealed by the divine word as interpreted by human reason. In the striking words of Ecclesiastics 32.23, 37.16, 13-14: “Let reason go before every enterprise and counsel before any action…And let the counsel of thine own heart stand…For a man’s mind is sometimes wont to tell him more than seven watchmen that sit above in a high tower….”

[22] Modern origins of “will” are discoverable in the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer, especially The World as Will and Idea (1818). For his own inspiration, Schopenhauer drew freely upon Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Later, Nietzsche drew just as freely and perhaps more importantly upon Schopenhauer. Goethe was also a core intellectual source for Spanish existentialist Jose Ortega y’Gasset, author of the singularly prophetic twentieth-century work, The Revolt of the Masses (Le Rebelion de las Masas;1930). See, accordingly, Ortega’s very grand essay, “In Search of Goethe from Within” (1932), written for Die Neue Rundschau of Berlin on the centenary of Goethe’s death. It is reprinted in Ortega’s anthology, The Dehumanization of Art (1948) and is available from Princeton University Press (1968).