There is no doubt that Morocco occupies a strategic position in its region. As a matter of fact, it sits on the crossroad of many cultures, religions and civilizations, and has through centuries become a true melting pot of so many ways of life and human beliefs, not to mention, obviously, races and ethnic groups. Because of this highly-interesting brassage de cultures (mixing of cultures,) Moroccans have masterfully acquired the ability and the predisposition to accept the other, no matter how complex his difference might be and how alien his “otherness” is.

The Moroccan sense of tolerance

Moroccans by nature are accommodating, open, friendly, available and very tolerant of other people and their cultures. But, their most important quality, by far, is their innate ability to welcome in other life experiences and cultural currents that obviously are not in contradiction with their entrenched beliefs, digest them and adapt them to their lives. As a result, Morocco is and has always been, also an open forum for dialogue and exchanges between the peoples of the Mediterranean and the sub-Saharan region.

A material proof of this is that its languages and cultures are full of loan words, tales, beliefs, stories, myths and traditions that originated in the other religions of the book. The Finnish anthropologist and ethnographer Edward Westermarck has masterfully documented this in his opus entitled “Ritual and Belief in Morocco” (2 volumes) that was published in the first half of the twentieth century.

Indeed, they have interacted positively with the Phoenicians, the Romans and many other races and have made beneficial exchanges with them, and today one still witness vestiges of these human interactions in the idioms, the customs and the beliefs, and not to mention the remains of entire cities such as Volublis, Lixus and others.

As early as the 8th century, horsemen coming from Arabia brought with them a new monotheist religion to the region: Islam, and gradually converted Christian and polytheist Amazigh people, with the exception of the Jewish inhabitants, who kept their monotheist belief. In turn, the newly converted Amazigh, under the leadership of their able general Tarik Bnou Ziyad, crossed the strait in 711 that, since, was called after him: Gibraltar Jabal Tarik (the mount of Tarik), and spread Islam in the Iberian Peninsula, that remained under Islamic rule until the advent of the Reconquista. After the fall of Grenada to the Catholics in 1492, both Muslims and Jews were kicked out of Spain and headed to Morocco where they found refuge. They were welcomed in by the locals and managed to prosper and occupy important posts in the government besides thriving in trade and finance.

Moroccan dynasties such as the Almoravids (1040-1147) and the Almohads (1121-1269), after the long and painful Islamization of the country, grew in power and moved southward spreading this new religion in sub-Saharan Africa by persuasion and, at times, by subjugation of the African people. Subsequent Berber an Arab dynasties of Morocco indulged in the unfair trade of exchange of salt against gold, enrolled the locals in their armies and brought home many others as slaves, they were known as Gnawa. The African slaves, to keep their culture alive, played in secret their transe music and practiced rituals of exorcism known as lila. Centuries later, when they were freed, the Gnawa, formed religious brotherhoods and travelled all over the country playing their music for subsistence. Today, their music and culture is gone global, thanks to the yearly festival organized in Essaouira around May or June and attended by thousands of people in search of Sufi exhilaration.

Sefrou, this wonderful “Little Jerusalem”

Judaism and Jews are as old as the country itself. Indeed, their first influx dates back to 70 AD and lived continuously in Morocco until their massive migration to Israel, on the aftermath of the creation of this state in 1948. They dwelled all over the country in villages, towns and cities and lived on commerce, trade and finance. Because of their wide experience in international trade, Moroccan Sultans appointed them as their financial and commercial agents: tujjar as-sultan. During the Second World War when the Nazi-occupied France wanted to prosecute them, the late King Mohammed V resisted the order and called for the prosecution of all Moroccans, if this were to happen, on the ground that they are no different from his other subjects, of whose safety he was responsible.

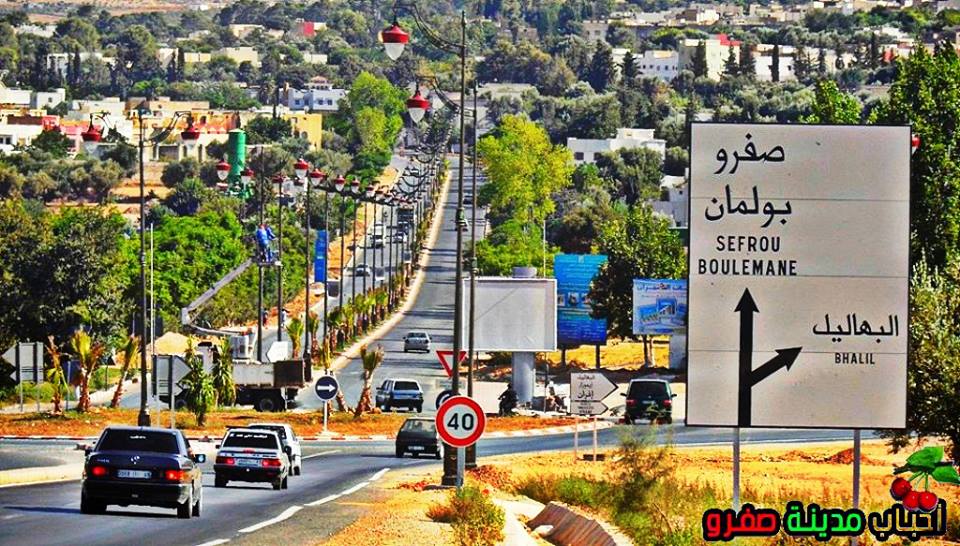

A good example of interfaith dialogue in Morocco can be witnessed in the city of Sefrou situated thirty Kilometers south of the spiritual capital of Morocco, Fes. In Sefrou lived Muslims and Jews in good harmony door to door and practiced their religious rituals in unison to the extent that it was difficult to tell what is Islamic and what is Jewish. What is more, they venerated the same saint buried in a grotto in a neighbouring mountain. The site was tactfully called “ Kaf al-moumen” ( the grotto of the faithful) because it was a religious sanctuary for both Muslims and Jews and times of worships in this area were equally divided.

The example of Sefrou, known by the name of Little Jerusalem because of its large Jewish population in the first part of the last century, is not unique in its kind in Morocco; it is found in other places like Debdou, Azrou, Fes, Rabat, Meknes, Marrakesh, etc…. In all these places lived large communities of Jews who practiced their faith and trades in complete peace and harmony. They were full Moroccans and as such enjoyed the full rights and obligations of their Muslim brethren.

Plural Morocco

At the turn of the 20th century, Morocco was subjected to European colonialism and the country was divided up between the French and The Spaniards who, over 50 years of Protectorate regime left a lasting imprint on the language, the culture and way of life of Moroccans, still vivid nowadays.

Summarizing the different external influences on Morocco, the late King Hassan II eloquently stated that his country is a tree that has its roots in Africa, the trunk in the Arab-Muslim world and its branches in Europe. Today, Moroccans proudly highlight their multiple and composite identity: Amazigh, Arab, Islamic, Jewish, African, Andalusian and Mediterranean and their time-old tolerance and acceptance of the other.

Following in the steps of his late father the late King Hassan II treated Moroccan Jews with great deference. He appointed one of them, André Azoulay, as a royal advisor and was instrumental in initiating political contacts between Palestinians and Israelis that led to the Oslo Accords in 1993 which kick-started the Oslo process.

The present King Mohammed VI is no different from his predecessors, he is a man of dialogue and coexistence and Morocco today is a haven of peace and coexistence between all religions and cultures, which is reflected in gold in the preamble of the Moroccan constitution of 2011:

“A sovereign Muslim State, attached to its national unity and to its territorial integrity, the Kingdom of Morocco intends to preserve, in its plentitude and its diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic [saharo-hassanie] components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences [affluents]. The preeminence accorded to the Muslim religion in the national reference is consistent with [va de pair] the attachment of the Moroccan people to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialog for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world”

Taking pride in Moroccan Jewish legacy

Morocco today is the only country in the Arab world that is proud of its Jewish legacy and generally speaking Moroccans regret openly the departure of Jews during the period 1948-1973 and this was illustrated remarkably in a documentary of 86 minutes entitled: “Tinghir-Jerusalem, the echoes of the Mellah,” made by Kamal Hachkar and screened worldwide. Officially, since the time of the late king Hassan II, all Moroccan Jews who left still hold Moroccan nationality and can come back to the country whenever they feel like it.

On the official level, The Moroccan Government, at the initiative of king Mohammed VI, has launched in 2010 a program of the rehabilitation of Jewish cemeteries, synagogues and other monuments, and as such 167 sites have been refurbished in 14 regions and a book titled “Rehabilitation of Morocco’s Jewish Cemeteries – The House of Life” was presented to the general public on February 2015 at the Arab World Institute (IMA) in Paris, as part of the exhibition-event “Contemporary Morocco.” For Serge Berdugo, The representative of the Moroccan Jewish community in the country:

“This has a strong symbolic and highly religious significance and reflects the commitment of the Kingdom to the values of moderation, dialogue and respect for others,” he noted. “It is the expression of a reality and a culture rooted in the long history of the Kingdom,”

Besides, today Morocco is the only country in the Arab world that has a museum located in Casablanca and that is exclusively dedicated to the traditions and material culture of the Jews that dwelled in the country for over two millennia and are still living in it in total peace, dignity and respect, though their population has dwindled from 250,000 in 1947 to 5,000 currently. The Moroccan Jewish community is located mostly in Casablanca and is known to be very active in the development of the country economically speaking and its tremendous patriotism.

American University. Morocco: A Country Study. Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1985.

Bowles, Paul. Morocco . New York : H. N. Abrams, 1993.

Cook, Weston F. The Hundred Years War for Morocco:Gunpowder and the Military Revolution in the Early Modern Muslim World. Boulder, Colo. : Westview Press, 1994.

Findlay, A. M. Morocco . Oxford, England : Clio Press, 1995.

Hoisington, William A. Lyauatey and the French Conquest of Morocco. New York : St. Martin’ s Press, 1995.

McDougall, James (ed.). Nation, Society and Culture in North Africa. London : Frank Cass Publishers, 2003.

Munson, Henry. Religion and Power in Morocco. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993.

Park, Thomas Kerlin. Historical Dictionary of Morocco . Rev. ed.Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1996.

Pazzanita, Anthony G. Historical Dictionary of Western Sahara .2nd ed. Metuchen, N.J. : Scarecrow Press, 1994.

Pennell, C. R. Morocco Since 1830 : A History. New York : New York University Press, 1999.

Wagner, Daniel A. Literacy, Culture, and Development:Becoming Literate in Morocco . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1993.