Jordan’s King Abdullah just announced that he informed Israel “of an end to the application of the peace-treaty annexes regarding al-Baqura and al-Ghumar.” The king was referring to a small area in Naharayim in Israel’s north and the Tzofar enclave in the Arava in Israel’s south, both of which were leased from Jordan in the 1994 peace agreement between Jordan and Israel.

The announcement by Abdullah immediately drew international headlines and fears that this could cause a rupture in relations between the two countries. Jordan, along with Egypt, is one of only two Arab countries with formal diplomatic ties with Israel, and despite a cold peace between the two peoples, they cooperate heavily on security-related matters in an increasingly hostile region.

Next year marks the 25th year, and therefore, the end of this specific agreement. If the parties do nothing, the agreement extends automatically for another 25 years. But the king has decided to pull out of those two clauses that pertain to the leases of these two areas.

“Al-Baqura and al-Ghumar have always been on top of my priorities,” he said. “Our decision is to end the annexes of the peace treaty based on our keenness to take all that is necessary for Jordan and Jordanians. Al-Baqura and al-Ghumar are Jordanian land and will remain Jordanian.”

In response, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said on Sunday, “We were told today that [Jordan] seeks to exercise this option in the 25th year. We will go into negotiations with them on the option of extending the existing agreement.”

Joshua Krasna, an expert on strategic and political developments in the Arab world at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategic Studies and a senior fellow in the Foreign Policy Research Institute, explained to JNS the complicated language of the peace treaty and history regarding these sites.

“The peace treaty does not discuss ‘leasing,’ but rather that the areas will fall under Jordanian sovereignty with Israeli private land-use rights, including unimpeded freedom of entry to, exit from and movement within the area,” he said.

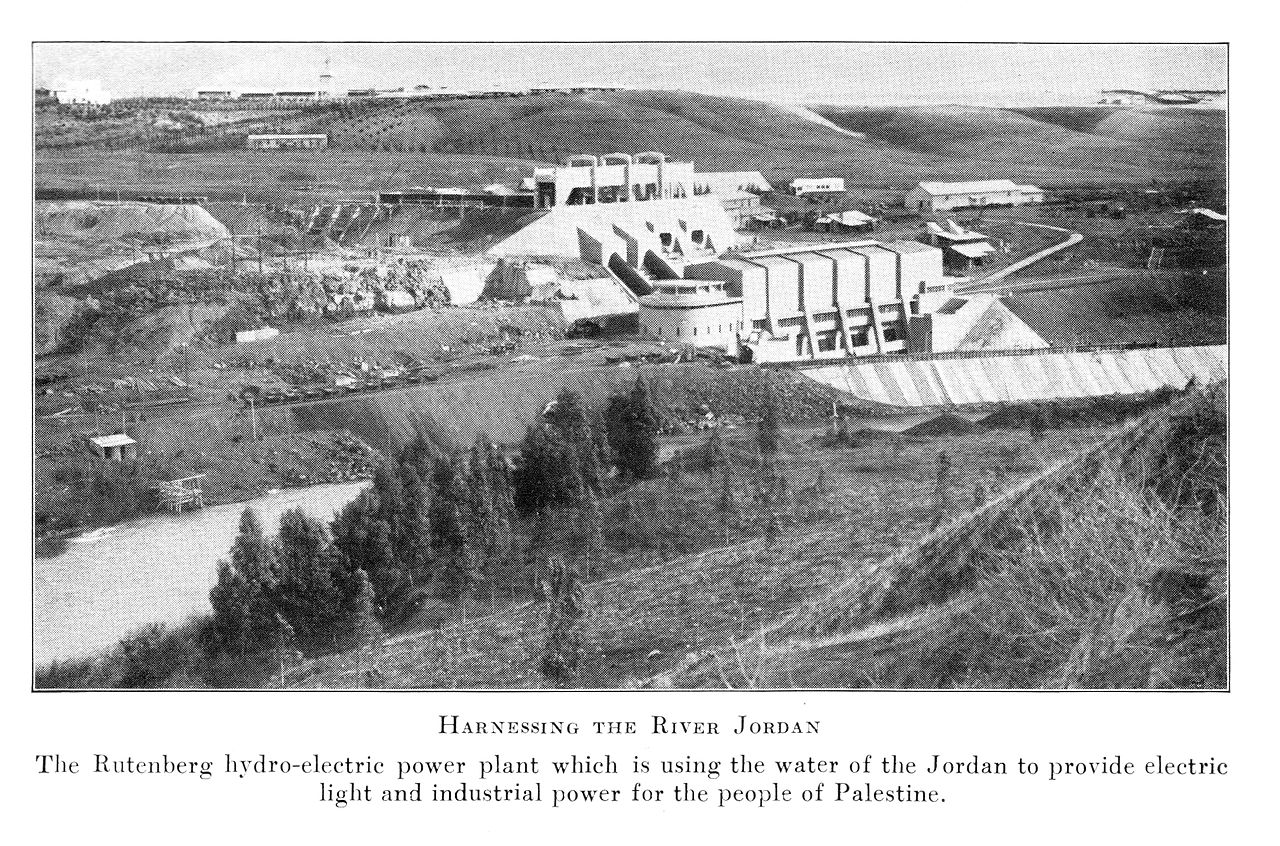

“Regarding the Naharaim site, as former Prime Minister Abdul Salam Majali noted, Israeli citizens have ‘ownership rights’ that date back to 1926, when Russian Jewish engineer Pinhas Rutenberg, who was a co-founder of the Haganah Jewish militia, obtained a concession for production and distribution of electric power.”

As such, Krasna believes that this will likely lead to a protracted legal and financial battle over the sites.

“This issue—that there are Israeli property rights in the northern disputed area—is not widely known in Jordan,” he said. “So the discussion of this area may well be protracted, and require compensation and even legal processes.”

‘The king is responding to public opinion’

Eran Lerman, vice president of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategic Studies, threw cold water on all the hype that the media has created around this issue. He told JNS that “nothing is being cancelled. The arrangement was for 25 years, and it will expire next year. It would have been surprising if the king did not claim what is his [and perhaps leave open the option of higher renumeration for these plots]. He knows all too well Israel will not quarrel with him over this.”

Similarly, Uzi Rabi, director of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University, told JNS that this move by the king was meant to pacify certain sectors in Jordan.

“This is not more than a PR exercise to his own people, as he wishes to please some trade unions and other unsatisfied sectors in Jordan. We have a year to work this out and Israel has the tools to make this all work out,” he said.

Nevertheless, the move by Jordan comes after tensions have been exacerbated between the two countries in the past year. In July 2017, an incident at the Israeli embassy in Jordan that led to the deaths of two Jordanians at the hands of an Israeli security guard caused a break in diplomatic relations for several months. The nations have also faced off in recent years regarding the status of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, where Jordan retains administrative and religious control through the Islamic Waqf.

At the same time, Abdullah Swalha, founder and director of the Center for Israel Studies in Jordan, told JNS, “I don’t think this will harm the bilateral relations between Jordan and Israel. This is a normal and regular agreement. Jordan used its legal rights to not renew the agreement.”

Swalha noted two reasons for the motivation behind the decision. The first, he said, is Jordan’s legal rights and the practicing of sovereignty over its land. The second are the demonstrations in the streets of Jordan over this issue.

“During the last two years,” he said, “there has been an ongoing campaign in Jordan asking the government to cancel this agreement. Just last week, over 80 members of Jordan’s parliament signed a petition asking the king not to renew the agreement. So the king is responding to public opinion.

“To people who say this will harm relations between the two countries, I don’t agree with them,” he continued. “There is exaggeration in the Israeli media about this decision. It’s not a political decision. It is a legal decision.”

At the end of the day, he said, Jordan will not destroy its peace agreement with Israel over two small tracts of land, and equally, Israel will not jeopardize good relations with a former enemy just to hold onto these areas.

Swalha reassured that “the relations between Jordan and Israel are strategic, and very important.”