In life, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was an outspoken friend of the Jewish people and an admirer of the nascent nation of Israel.

King spoke to numerous Jewish audiences, frequently linking Jewish history to the struggle of African-Americans to overcome racism.

We are just past the King Day holiday and on the cusp of Black History Month in February of the year that marks the 50th anniversary of King’s death. He was killed by a single rifle shot at a minute past 6 p.m. on April 4, 1968, as he stood on a balcony at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where he had gone in support of the city’s striking African-American sanitation workers. The night before, King delivered what came to be known as his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. He was 39.

How King’s relationship with the Jewish people might have evolved is a matter of speculation. What is certain are the words King spoke while alive.

King first appears in an online archive of The Southern Israelite (which was renamed the Atlanta Jewish Times in January 1987) on Page 2 of the July 25, 1958, edition, reporting on his May 14 speech in Miami Beach to the national convention of the American Jewish Congress.

“My people were brought to America in chains. Your people were driven here to escape the chains fashioned for them in Europe. Our unity is born of our common struggle for centuries, not only to rid ourselves of bondage, but to make oppression of any people by others an impossibility,” King said.

“There are Hitlers loose in America today, both in high and low places,” he said further on. “As the tensions and bewilderment of economic problems become more severe, history(’s) scapegoats, the Jews, will be joined by new scapegoats, the Negroes. The Hitlers will seek to divert people’s minds and turn their frustrations and anger to the helpless, to the outnumbered. Then whether the Negro and Jew shall live in peace will depend upon how firmly they resist, how effectively they reach the minds of the decent Americans to halt this deadly diversion. …

“Some have bombed the homes and churches of Negroes; and in recent acts of inhuman barbarity, some have bombed your synagogues — indeed, right here in Florida.”

Three months later, on Oct. 12, 1958, The Temple in Midtown Atlanta was bombed.

The Temple bombing was seen as retaliation by white supremacists for Rabbi Jacob Rothschild’s support of the civil rights movement. Rabbi Rothschild and his wife, Janice, became personal friends of King and his wife, Coretta.

When King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on Oct. 14, 1964, a dinner in his honor was planned by a committee composed of Rabbi Rothschild, Archbishop Paul John Hallinan of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Atlanta, Atlanta ConstitutionEditor Ralph McGill and Morehouse College President Benjamin E. Mays.

Tickets for the dinner, scheduled for Jan. 27, 1965, at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel, were $6.50 apiece.

When Atlanta’s white, conservative business community showed little interest in honoring King, a not-so-veiled “you need us more than we need you” message from the highest echelons of Coca-Cola’s Atlanta headquarters spurred the sale of 1,500 tickets.

In his introduction of King, Rabbi Rothschild said: “In striving to create a world of brotherhood and dignity for every man, in seeking to achieve contentment and fulfillment in every human heart, he sets an example of conduct and goals for all men. For surely without tranquility of the human soul then the dream we have of a peaceful world lies forever beyond the grasp of mankind. …

“Yes, you gather to honor a man, but you honor a city as well — a Southern city that has risen above the sordidness of hate prejudice. You — rich and poor, Jew and Christian, black and white, professional and lay, men and women from every walk of life — you represent the true heart of a great city. You are Atlanta. You — and not the noisy rabble with their sheets and signs that threatened to slog sullenly the sidewalks beyond these doors.”

King told his audience: “Anyone sensitive to the present moods, morals and trends in our nation must know that the time for racial justice has come. The issue is no longer whether segregation and discrimination will be eliminated but how they will pass from the American scene. The deep rumbling of discontent that we hear today is the thunder of disinherited masses, rising from dungeons of oppression to the bright hills of freedom.

“These developments should not surprise any student of history. Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The yearning for freedom eventually manifests itself. The Bible tells the thrilling story of how Moses stood in the Pharaoh’s court centuries ago and cried, ‘Let my people go.’ This is a kind of opening chapter in a continuing story. The present struggle in our country is a later chapter in the same unfolding story. Something within has reminded the Negro of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained.”

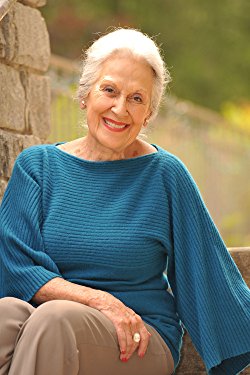

When someone, in this case King, is a friend, “it’s hard to conceive of that person as being a real icon,” said Janice Rothschild Blumberg, the rabbi’s widow.

“My first impulse is that his legacy is so much bigger than what Jews think about,” she said. “You know the Jewish expression, from Moses to Moses (Maimonides), there’s no one like Moses. I really believe that decades from now, Christianity will have that kind of expression, from Martin Luther to Martin Luther King, because he made this monumental change in Christianity.”

She said his message “is that you judge people by the content of their character, and it resonates so with me because my mother had taught me that, in almost the same words. That’s the secret to getting along in this world.”

Rothschild Blumberg added: “King was different. I would say better, not just different. He made it possible for people, for more people to think more carefully about other people having the same qualities.”

The Temple today is led by Rabbi Peter Berg.

Former Fulton County Board of Commissioners Chairman John Eaves is a member of Rabbi Berg’s congregation.“When Dr. King was assassinated 50 years ago, a majestic moral force in America was silenced,” Rabbi Berg said. “But his spirit has grown even stronger through the years. There are those among us who try to compartmentalize their loyalties in America and in the world. Some of us mistakenly say, ‘If I am a Jew, I must direct all my energy and giving and concerns to the welfare of my people.’ Others say, ‘If I am African-American, my only brothers and sisters who truly understand me are my family of African-Americans.’ And others of different creeds and colors offer similar, narrow philosophies. This kind of parochialism never worked in the past and will certainly not work in our world today. Dr. King taught us that we are all God’s children. If we don’t work together, if we don’t care for each other and work for the liberation of all suffering humanity, then we are neither Jews nor African-Americans nor authentic children of God.”

“I am an African-American, and I am a Jew. They are not mutually exclusive identities, for one impacts the other in my interpretation of the life and message of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,” said Eaves, whose grandfather converted to Judaism.

“I believe that Dr. King should be viewed by Jews in the same manner in which we view other great men and women of our faith who were a part of the prophetic tradition. An analysis of King’s speeches reveals that he spoke of liberation like Moses, he championed justice like Amos, he advocated for the poor like Micah, he devoted his life for saving his people like Esther, and he embraced the messianic ideal of Malachi,” Eaves said.

A similar comment, however, was King’s reported rebuke to criticism of Zionists during a dinner conversation with students from Harvard University while he was in Boston on Oct. 27, 1967, during a stop on a fundraising tour for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference(created as an outgrowth of the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott of 1955-56).King made numerous statements that evince support for the Jewish people, though one written in a supposed “Letter to a Zionist Friend” — “Anti-Semitism, the hatred of the Jewish people, has been and remains a blot on the soul of mankind. In this we are in full agreement. So know also this: Anti-Zionist is inherently anti-Semitic, and ever will be so” — is believed by researchers to be a hoax.

Seymour Martin Lipset, then a professor of government and sociology at Harvard, was in attendance and wrote about the dinner in the December 1969 edition of Encounter magazine.

Lipset reported that when one of the young men present criticized Zionists (the dinner being four months after the Six-Day War), King said, “Don’t talk like that! When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism!”

A 1963 graduate of Emory University, Lois Frank has long been a leader in Atlanta’s Jewish community and nationally, most notably through the Jewish Council for Public Affairs.

To this day, she remains amazed that, as the chair of the Emory Student Colloquium, she cold-called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and got King to agree to speak.

She was no less amazed that day in May 1962 when she picked up Martin and Coretta King in her Volkswagen Beetle and found hundreds of students waiting when they arrived on campus.

King told an eventual audience estimated at 1,000 that “if democracy is to survive, all discrimination must be ended as it is destroying the soul of our nation,” the student newspaper, The Emory Wheel, reported.

“My memory of MLK’s talk at Emory, aside from the tremendous crowd that showed up with no support or encouragement from the university: … His speech was erudite, intellectual and framed in the language of university students … using philosophy, culture and even music to make his points. He was brilliant and inspirational,” Frank said.

“No question, my one takeaway was that he was masterful in speaking our language,” she said. “He was probably the first speaker/lecturer I heard outside of my professors who spoke on the level of challenging our intellects.”

King’s legacy is integral to the bus trips across America that Billy Planer leads through his Etgar 36 program.

The trips, which attract Jewish teens from across the country, begin in Atlanta and include visit to sites associated with the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Birmingham and Memphis.

Planer grew up at Ahavath Achim Synagogue in Buckhead and became its youth director, as well as youth director at congregations in Washington, D.C., and Highland Park, Ill.

“We are basically following in his footsteps the whole trip. The idea of building the beloved community is what we are trying to do when we teach the teens that when they engage with people they may disagree with, to try to find the humanity in the person on the other side of the table or political divide, so that while we may disagree, we don’t demonize, and we can continue to grow together into this more perfect union,” Planer said.

“King’s life still rings strongly with teens today. They know his quotes and his belief in nonviolence. They also enjoy studying the 1967-68 King, who was a more complicated figure than we celebrate today, so I think the teens like the conflict and the complicatedness of his life. We really drive home that the message and lessons of the civil rights movement did not end with passage of the Voting Rights and Civil Rights bills or his assassination, but it continues and is very relevant today when dealing with incarceration, marriage equality, distribution of economic wealth, etc.”

Hannah Podhorzer, a member of Congregation Bet Haverim, is a 21-year-old junior at Elon University in North Carolina.

“Martin Luther King was introduced to us as the central civil rights figure. I think he still is viewed that way by many of us,” Podhorzer said. “At the same time, I believe there is this curiosity about who else defined that time, maybe those who didn’t have entire textbook chapters dedicated to them or streets named after them. I certainly hold an interest in discovering further the names and stories that didn’t make it into our mainstream history textbooks.

“Nonetheless, I would say that I think of him as a mensch, and perhaps that is where his legacy lies with the Jewish people for my generation — serving as a historical display of the depths of that word.”

Fifty years ago, Israel’s representative in Atlanta had a less charitable view of King.

The Israel State Archive marked the 45th anniversary of King’s death by releasing documents that included a classified letter that the Israeli consul in Atlanta, Zeev Dover, sent in August 1962 to his embassy in Washington.

Dover wrote that he “places great importance on forming connections with the black leadership” (suggesting that books about Israel and Judaism be sent to black colleges), but “in my opinion the time is not yet ripe for his visit to Israel.”

King represented “the militant wing of the civil rights movement,” Dover reported, adding that important organizations “are not in agreement with him and oppose his methods” and that King had alienated moderate African-Americans.

A formal government invitation to King, who in 1959 had visited East Jerusalem holy sites and cities under Jordanian control, could harm ties with Southern states that felt threatened by King’s prominence in the African-American community, Dover wrote, advising that “in any case, we should not be the first country that gives King so-called international status.”

Dover suggested “shelving the idea until the right moment” and added, “Our efforts to enter into discussions with different factors in the black community must be done … without being overly conspicuous.”

The idea was shelved until early 1967, when plans were announced for King and perhaps 5,000 others to make a pilgrimage to Israel as an SCLC fundraiser.

Those plans were derailed by the war that began June 6 when Israel, under threat from its Arab neighbors, pre-emptively struck the armed forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Within days, Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria, the Gaza Strip from Egypt, and the eastern sector of Jerusalem, including the Old City, from Jordan.

Though some in the civil rights movement more militant than King identified with the Arab nations, in late May he had signed an open letter to President Lyndon B. Johnson published in The New York Times, urging American support for Israel.

Aides returned from a postwar trip to Israel suggesting that the visit go forward.

The contents of King’s July 24 conference call with advisers are known because the FBI wiretapped the phone of a key adviser, Jewish businessman and lawyer Stanley Levison.

In the aftermath of Israel’s victory, King said, “I’d run into the situation where I’m damned if I say this and I’m damned if I say that, no matter what I’d say, and I’ve already faced enough criticism, including pro-Arab. I just think that if I go, the Arab world, and of course Africa and Asia for that matter, would interpret this as endorsing everything that Israel has done, and I do have questions of doubt. … Most of it would be Jerusalem, and they have annexed Jerusalem, and any way you say it, they don’t plan to give it up.”

King could not shake his doubts.

“I frankly have to admit that my instincts, and when I follow my instincts, so to speak, I’m usually right … I just think that this would be a great mistake. I don’t think I could come out unscathed.”

Two months later, on Sept. 22, 1967, King wrote to Mordechai Ben-Ami, the president of the Israeli airline El Al, which was to handle part of the flight package.

“It is with the deepest regret that I cancel my proposed pilgrimage to the Holy Land for this year, but the constant turmoil in the Middle East makes it extremely difficult to conduct a religious pilgrimage free of both political overtones and the fear of danger to the participants,” King said.

He promised to revisit the plan the following year.

It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to know how King’s views on Israel might have changed, though statements in the months before his death, such those related to his decision not to visit Israel, offer hints.

On March 26, 1968, King addressed the 68th annual convention of the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly, in a question-and-answer session with Rabbi Everett Gendler.

King discussed both the Israeli-Arab conflict and why some African-Americans resented Jews.

“Probably more than any other ethnic group, the Jewish community has been sympathetic and has stood as an ally to the Negro in his struggle for justice,” King said.

“On the other hand, the Negro confronts the Jew in the ghetto as his landlord in many instances. He confronts the Jew as the owner of the store around the corner where he pays more for what he gets. In Atlanta, for instance, I live in the heart of the ghetto, and it is an actual fact that my wife in doing her shopping has to pay more for food than whites have to pay out in Buckhead and Lenox. We’ve tested it. We have to pay 5 cents and sometimes 10 cents a pound more for almost anything that we get than they have to pay out in Buckhead and Lenox Square, where the rich people of Atlanta live.

“The fact is that the Jewish storekeeper or landlord is not operating on the basis of Jewish ethics; he is operating simply as a marginal businessman. Consequently, the conflicts come into being.”

King acknowledged divisions over Israel within the civil rights movement.

“The response of some of the so-called young militants again does not represent the position of the vast majority of Negroes. There are some who are color-consumed, and they see a kind of mystique in being colored, and anything noncolored is condemned. We do not follow that course in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and certainly most of the organizations in the civil rights movement do not follow that course.

“I think it is necessary to say that what is basic and what is needed in the Middle East is peace. Peace for Israel is one thing. Peace for the Arab side of that world is another thing. Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all of our might to protect its right to exist, its territorial integrity. I see Israel, and never mind saying it, as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land almost can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security, and that security must be a reality.

“On the other hand, we must see what peace for the Arabs means in a real sense of security on another level. Peace for the Arabs means the kind of economic security that they so desperately need. These nations, as you know, are part of that Third World of hunger, of disease, of illiteracy. I think that as long as these conditions exist, there will be tensions, there will be the endless quest to find scapegoats. So there is a need for a Marshall Plan for the Middle East, where we lift those who are at the bottom of the economic ladder and bring them into the mainstream of economic security,” King said.

Nine days later, King was assassinated.

Dov Wilker, the Southeast regional director of American Jewish Committee, suggested that Jews have a somewhat narrow view of King.

“I think it’s about a champion of civil and human rights, a supporter of Israel and the Jewish people and the self-determination of Zionism,” Wilker said. “Nobody chooses to remember him about the work that he was doing before he died, around wages and economic reform and housing.”

“Coretta maintained Martin’s disdain for conflict, war and violence,” Frank said. “I feel sure they would be somewhat sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, but they were both totally supportive of the state of Israel and understood deeply the suffering of Jews before and after the state was established. They were thoughtful and very fair, not necessarily knee-jerk Liberation Theology proponents, as many pro-Palestinian human rights activists are today.”People don’t think about the fraying of the black-Jewish alliance from the mid-1960s civil rights movement, Wilker said. “We don’t talk about what the evolution of the relationship was, what the struggle was that King might have had within his own organizations toward the Jews. We’re able to look back and think positively.”

“I often wonder what Dr. King would be preaching about today if he was living amongst us still,” Rabbi Berg said. “How would he react to those who are so intolerant of others? What message would he have for a society that still neglects its children? Surely Dr. King would cry out against a society that neglects healing the sick, clothing the naked and feeding the poor. And we should too.”

“Dr. King was an unrelenting champion of peace. I believe Dr. King would have spoken out boldly for the two-state solution as he did against the Vietnam War,” Eaves said.

Jesse Benjamin was born in Israel and raised in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States before returning to Israel as a teenager. Today he is an associate professor in Kennesaw State University’s sociology department and its School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding and Development.

“I believe strongly that King would have been a strong and consistent critic of Israel had he lived on. … After 1967 and the Six-Day War (referred to by Palestinians as the Naksa, the setback), almost the entire progressive black world rapidly lost illusions of Israel as anti-colonial and shifted to siding consistently with Palestinians. This is undoubtedly what King would have done and is precisely what his close comrades, like the late Vincent Harding, did in fact do,” Benjamin said.

“As we meditate on King’s legacy for Jews 50 years later, I think the primary lesson is that the proud Jewish tradition of standing on the right side of history has been endangered by Western assimilation, identification with whiteness and with imperial privilege. Too often today, Jewish individuals, communities and organizations stand against social justice, on the wrong side of history, though it should be said that the exceptions to this general rule are finally growing, especially in the work of JVP (Jewish Voice for Peace). King’s legacy requires Jews and all people of conscience to fight against whiteness and white privilege, for all poor people’s rights, and return to visionary solidarities like those embodied in BLM (Black Lives Matter) and BDS (boycott, divestment and sanctions).”

“I try to honor the MLK legacy of really creating equality and inclusion and honoring individuals for their work to ensure that the voices of Jews of color and ethnically diverse Jews are celebrated,” Rabbi Abusch-Magder said. “We have an obligation to ensure that our community is as welcoming as we ask the rest of society to be and as inclusive as we hope the rest of society could be.”Ruth Abusch-Magder is rabbi in residence and education director for Be’chol Lashon, an organization that promotes racial and ethnic diversity in the Jewish community.

King “was a man who was capable of complex thinking and coalition building and really looking into where people were. Had he lived he would have continued with those pieces,” she said. “He would have been a different kind of force for good in our world. His intellect and his strategic capacity were exceptional, and those would have been a blessing to all of us in America.”

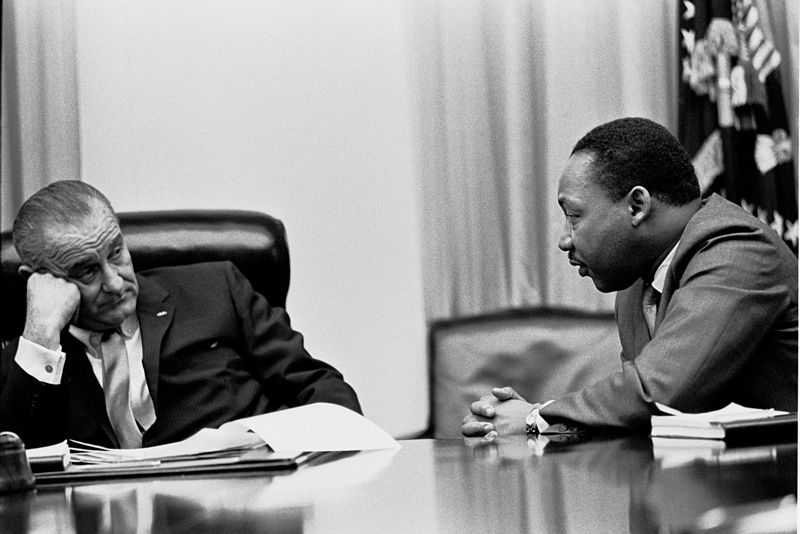

Main Photo by Yoichi Okamoto [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons