Prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Morocco was home to some 250,000 Jewish inhabitants. Moroccan Jews had arrived in the country by means of two major waves of immigration, the first following the Roman-imposed exile in 70 A.D., the second following the 1492 Spanish Edict of Expulsion. Through nearly two millennia of cohabitation and cultural exchange, the Jews had become an integral part of Moroccan society. From the influence they exerted on the development of Amazigh/Berber tribal consciousness and religious beliefs to their central economic and political position during the Alaouite Dynasty (1631-present), Moroccan Jews have played a significant role in all stages of recorded Moroccan history. However, within a matter of decades following Israel’s Declaration of Independence, this entire substratum of Moroccan culture and society had all but vanished. Today, around 5,000 Jews remain in Morocco, the majority of which are concentrated in Casablanca, the country’s commercial and industrial capital.

Nature of Jewish migration out of Morocco

In contrast to some of the historical narratives advanced by both Israeli and Arab scholars, the nature of Jewish migration out of Morocco is a complex and multi-causal historical phenomenon. I argue that a combination of internal push-factors and external pull-factors are responsible for the Moroccan Jewish exodus. Push-factors such as overt violence, discriminatory governmental policies, and a general mood of anti-Jewish sentiment induced Jewish emigration. However, this process was facilitated and catalyzed by a number of important pull-factors to Israel, France, and Canada, and the United States orchestrated by the Jewish Agency and the Israeli government.

Before delving into a more detailed analysis of these processes, it is first necessary to briefly discuss what is meant by push-pull factors. In the study of human populations and ethnography, push-factors are defined as the trends, institutions, or other stimuli that encourage movement out of a given societal unit. Conversely, pull-factors constitute the reasons people are attracted to a different setting.[i] These concepts stand as the conceptual basis for this paper’s analysis.

Furthermore, the scope of this study has been parameterized between two key dates—1948 and 1973—due to their historical significance and use as clear temporal markers. The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 is nearly unanimously cited as the leading reason for the migration of Arab Jews from their home countries to the newly founded Jewish State. Likewise, the Yom Kippur War of 1973 marked the close of an important phase in the relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Additionally, though Jewish emigration from Morocco occurred prior to 1948 and has continued to the present day, scholars estimate that more than 90% of the emigration occurred between these two dates.[ii] For these reasons, this study will concentrate on events spanning this twenty-five year period.

Violence towards the Jews

The most immediate cause of emigration from Morocco beginning in 1948 until the end of the French Protectorate in 1956 was a series of violent riots and pogroms targeted at Jewish communities across the country. Given the acts of extreme violence directed at Jews at the hands of their Arab neighbors across the Middle East following Israeli Independence, these events sowed the seeds of fear and distrust for Moroccan Jews. The clearest example of these jarring episodes are the pogroms that occurred in the towns of Oujda and Jerada in June, 1948. Located in northeastern Morocco near the Algerian border, Oujda served as a transit point for thousands of Jews migrating out of Morocco to Israel and France. This daily movement of Jews through the city put local inhabitants on edge, which further exacerbated by the high degree of regional tension caused by the fighting occurring in Israel between Jewish and Arab forces. Rioting broke out in Oujda on June 7th and continued until authorities forcefully imposed order hours later. In this period, five Jews were murdered and dozens injured. Unrest spread to the nearby town of Jerada, where a mob murdered 38 Jews until the army gained control of the situation on June 8th.[iii] Though more minor in duration and casualties figures, riots and general violence such as the events in Oujda and Jerada continued until the end of the Protectorate in 1956.[iv]

On this topic, Lela Gilbert writes in the Jerusalem Post:[v]

“There were bigger threats too, including mysterious disappearances. First her father’s best friend vanished. Then one of Dina’s cousins, a remarkably beautiful 14-year-old girl, also disappeared, never to be seen again. In the Moroccan Jewish community, such things weren’t exactly unusual. And they happened more and more frequently after 1948, when Israel declared itself an independent state. At that moment, the centuries-long, low-grade oppression Jews experienced in their role as dhimmis under Muslim rule was ignited into ugly confrontations, humiliation and random attacks. These episodes sometimes exploded into full-blown pogroms in which hundreds were killed or wounded.”

These riots represented a resounding wake-up call to Moroccan Jews. On one hand, the community was appalled that their Muslim compatriots were capable of such vicious acts of violence. Similar events were occurring across the Middle East, many with greater frequency and magnitude. Likewise, in the years immediately following the close of World War II, the atrocities committed by the Nazis against European Jews were fresh in the mind of their Moroccan counterparts. The combination of a sudden distrust of their neighbors and fear for the worst prompted thousands of Jews to immigrate to Israel or France.[vi]

Additionally, many Jews were highly critical of the official response to these riots. The fact that it took the police and army hours or days to restore order in the above-mentioned riots provoked fierce criticism of the governmental response thereto. Likewise, though still disputed by scholars of Moroccan history, allegations exist that implicate Moroccan pro-nationalist actors in inspiring and encouraging violence against Jews. These allegations, founded or not, led many Jews to doubt the government’s ability and willingness to provide due protection to their kinsmen. As such, emigration began en-masse to France, Israel, and beyond.

Official Policies

In 1956, Morocco gained independence from France and the new country began the task of nation-building with King Muhammad V of the historic Alawite line at the helm. The change of political control from France to the Alawite line led to drastic changes for the country’s Jewish population. Whereas under the Protectorate ultimate power lay vested in secular institutions, independent Morocco was declared an Arab-Islamic state where final political authority resided in the monarchy. In 1958, Morocco joined the Arab League, thus aligning it politically with the Pan-Arabism trend sweeping the region.[vii] Though Jews were granted citizenship and guaranteed full rights under the new Moroccan Constitution, the country’s explicitly defined Arab-Islamic identity sparked a process of cultural marginalization. Likewise, it made the prospect of immigration to Israel—an avowedly Jewish State—more appealing than remaining at the societal periphery of Morocco, at least in terms of cultural and religious recognition.

Morocco’s move to join the Arab League in 1958 further catalyzed Jewish emigration. When pressured by the other member states to assume the League’s anti-Israel policy, King Muhammad V banned immigration to Israel and imposed travel restrictions on Moroccan Jews such as the refusal to issue passports or other necessary documents. This particular royal policy was perhaps the most important push-factor behind Jewish emigration from Morocco. Firstly, by ceding to the Arab League’s political pressure, it appeared as though Morocco was moving into the Pan-Arabism ideological sphere. Moroccan Jews feared that the type of vociferous anti-Israel rhetoric of influential Pan-Arab figures such as Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser would be assumed by the Moroccan government, thus posing a threat to their political freedoms, property, and general well-being. Furthermore, the steps taken by the Moroccan government to restrict its Jewish citizens’ freedom of movement was regarded as a grave violation of both their rights and trust in the new state. Though officially banned, clandestine immigration continued throughout this period through smuggling and Mossad activities, which will be discussed in greater detail below.

On January 10, 1961, one such smuggling ship named The Egoz sailed out of Alhoceima, bound for Spain with 42 Jewish immigrants illegally aboard. The ship capsized in open water and, tragically, no crew members or passengers survived the ordeal. This event provoked immediate and intense criticism of the Moroccan government’s immigration policy worldwide. In response to the international reaction to the Egoz disaster and King Muhammad V’s death in February 1961, his successor, King Hassan II, reversed the royal ban on immigration and lifted travel restriction on Moroccan Jews.[viii] However, the early years of Jew’s experience under the rule of King Muhammad V alienated them from the Moroccan monarchy and led them to distrust the government and pro-nationalist forces. This expedited the emigration process and the urgency it assumed in the minds of Moroccan Jews.

The Jewish Agency in Morocco

After 1948, Israeli “Absorption Policy” as coordinated by The Jewish Agency did not consider Moroccan Jews as priority Jews for emigration because of their stability in Morocco. According to Johnathan Kaplan, the policy was selective:[ix]

“The Israeli authorities dealing with immigration gave first priority to the Holocaust survivors and to those Jewish communities in Moslem countries that required immediate evacuation, namely Yemen and Iraq. With regard to other large Jewish centers such as Morocco, the conditions of which did not seem to warrant such a policy, selective criteria were applied to determine who would be sent to Israel. In November 1951, the Jewish Agency, the body that carried the major responsibility for immigration and absorption, set down guidelines for the selection of immigrants. These criteria continued the pre-state principles of “pioneering” immigration and favored young, healthy people who would settle and work the land. In the reality of the 1950s, this meant that while the young and strong would be brought to Israel, the older and weaker elements would be left in Morocco. Although the policy of selection became the subject of intense public debate in Israel and the regulations were soon revised, the principle of selection was maintained at least until 1956.”

Through the operation of a number of pull-factors, Jewish immigration to Israel and the West peaked in the period between 1961 and 1967, resulting in the flight of more than 100,000 Jews in this six-year span.[x] One of the most important factors driving this vast movement was the work of the Jewish Agency, registered as the Kadima Office in Casablanca. The Jewish Agency was an international Zionist organization promoting the resettlement of diaspora Jewry in Israel, and had an array of financial, political, and material resources at its disposal.

The Jewish Agency coordinated all aspects of migration from Morocco to Israel. It sent representatives to distant rural districts across the country in order to establish contacts with Jewish communities. Its efforts were concentrated on enabling lower and middle class Jews to emigrate, who would otherwise be unable to due to financial and logistical obstacle. The Jewish Agency’s work was particularly pronounced in the poor, southern regions of Morocco where poverty and isolation hampered mobility of local Jewish communities. Once contact had been established with an agency representative, Jews were afforded help in navigating official channels in order to obtain passports and required travel documents. Transportation was provided that took them to urban hubs such as Casablanca, Essaouira, and Tangier, where ships and planes were chartered to take them to Israel. They were then resettled in vast migration camps and settlement towns across Israel, many in the sparsely inhabited Negev desert.[xi]

The work of the Jewish Agency played a central role in providing the financial and logistical means necessary for the bulk of Moroccan Jews to migrate to Israel. Their outreach to socio-economically disenfranchised communities and coordination of the cumbersome process are largely responsible for major wave of emigration that occurred between 1961 and 1967. Likewise, the pro-Israel, Zionist ideology they advanced spoke to the latent religious sentiments of Moroccan Jewry, providing a strong spiritual impetus for resettlement in Israel.

Mossad’s action in Morocco

Though the Jewish Agency was the public face for the immigration of Moroccan Jews to Israel, Mossad, the Israel Defense Force’s covert operations wing was a significant behind-the-scenes actor in this process. Scholars estimate that Mossad was responsible for the illegal immigration of some 30,000-50,000 Jews between 1958 and 1961. In 1961, Mossad launched Operation Mural, a covert effort aimed at bringing Jewish children to Israel following the above-discussed Egoz disaster. Between March and June 1961, some 530 Jewish children were brought to Israel under the guise of an NGO-sponsored vacation in Switzerland. Agents were enlisted and deployed to Morocco in order to find families willing to send their children to Israel. On selected dates, the children were flown on chartered flights to Switzerland by the Organization for the Rescue of Children. However, instead of returning to Morocco, they were flown from Switzerland to Israel, where they were naturalized and resettled upon arrival. Though not made public until 1984, Operation Mural stands as an important benchmark in modern Moroccan Jewish history in that it is the first openly acknowledged work by Mossad on Moroccan soil.[xii]

According to the electronic journal “Revolvy”:[xiii]

“In 1954, Mossad had established an undercover base in Morocco, sending agents and emissaries within a year to appraise the situation and organize continuous emigration. The operations were composed of five branches: self-defense, information and intelligence, illegal immigration, establishing contact, and public relations. Mossad chief Isser Harelv visited the country in 1959 and 1960, reorganized the operations, and created a clandestine militia named the “Misgeret” (“framework”).

Emigration to Israel jumped from 8,171 persons in 1954 to 24,994 in 1955, increasing further in 1956. Between 1955 and independence in 1956, 60,000 Jews emigrated. On 7 April 1956, Morocco attained independence. Jews occupied several political positions, including three parliamentary seats and the cabinet position of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. However, that minister, Leon Benzaquen, did not survive the first cabinet reshuffling, and no Jew was appointed again to a cabinet position. Although the relations with the Jewish community at the highest levels of government were cordial, these attitudes were not shared by the lower ranks of officialdom, which exhibited attitudes that ranged from traditional contempt to outright hostility. Morocco’s increasing identification with the Arab world, and pressure on Jewish educational institutions to arabize and conform culturally added to the fears of Moroccan Jews. Between 1956 and 1961, emigration to Israel was prohibited by law; clandestine emigration continued, and a further 18,000 Jews left Morocco.”

In 1961, Mossad initiated the far-more ambitious Operation Yachin, which lasted until 1964. Operation Yachin constituted a secret agreement between Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Moroccan King Hassan II by which Morocco would be paid indemnities for each Jewish immigrant to Israel. In exchange, Israel was given the freedom to charter boats and planes from Casablanca and Tangier that ferried Jews first to neutral-countries such as Italy and France, wherefrom they were brought to Israel. Both governments pledged to keep the nature of the operation secret, lest Morocco’s Arab neighbors retaliate for its break of Arab League policy and attempt to sabotage migration efforts. Between 1961 and 1964, some 100,000 Jews were brought to Israel, France, and Canada through Operation Yachin.[xiv]

The Moroccan Jewish legacy

Between 1964 and 1973, Jewish emigration from Morocco steadily continued. The Moroccan regime’s legalization of immigration enabled those with financial means to readily do so. As Moroccan Jewish communities took root in Israel, France, Canada, and the United States, the country’s remaining Jews were provided an additional social impetus to leave. The Six-Day War of 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973 left Moroccan Jews wary of Arab governments while unofficial anti-Semitism escalated in the public sphere across Morocco. By 1973, Moroccan Jews had little reason to remain. King Hassan II’s repressive Years of Lead were under way, and citizen’s human rights and personal freedoms were daily violated by the regime. Moroccan Jewish communities began to thrive abroad, offering the prospect for a new life with abundant economic and social opportunities. By 1973, less than 30,000 Jews remained in Morocco.[xv]

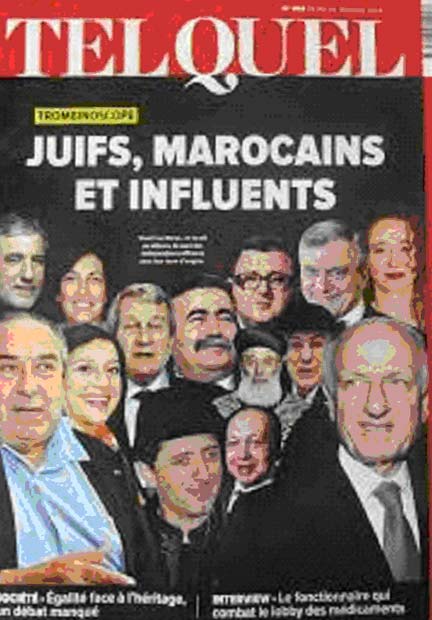

Today, some 5,000 Jews remain in the country. Though the late King Hassan II has called those of Moroccan Jewish ancestry to return and has promised full citizenship to them, few if any have accepted his invitation. However, more than any time before, the Moroccan state has displayed its commitment to the creation of a pluralistic state dedicated to the preservation of human rights—that to freedom of religion included. For instance, the King Mohammed VI’s 2011 Constitutional Reforms recognize the importance of Morocco’s Hebraic heritage in the county’s cultural development. André Azoulay, hailing from Mogador-based Jewish origins, is one of the King’s chief advisors and represents one of the most influential voices in the establishment. As a number of Middle Eastern and North African states have slipped into anarchy and fierce sectarian violence, Morocco’s commitment to tolerance and diversity stand as a beacon of hope.

In fine

The above-analysis has striven to address the diverse set of factors that facilitated that emigration of some 250,000 Moroccan Jews over a twenty-five-year period. These factors may be divided into those that drove Jews from Morocco—namely violence and discrimination—and those that attracted them to life in Israel, France, Canada, the United States, and beyond. The interaction between these competing forces resulted in one of the largest population movements of the 20th century. Though Jewish life seems increasingly limited and infeasible across the Diaspora world, Morocco under the rule of King Mohammed VI stands as an exception. Morocco’s Jewish heritage has yet to disappear and, God willing, will endure for years to come.

End notes:

[i] http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/migration/migration_trends_rev2.shtml

[ii] Prior to 1948, estimates place Morocco’s Jewish population at 250,000. After the close of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, less than 50,000 Jews remained. See

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html#8

[iii] http://www.sephardicgen.com/databases/oujdaDjeradaSrchFrm.html

[iv] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html#8

[v] http://www.jpost.com/Features/In-Thespotlight/The-Nakba-of-Moroccos-Jews

[vi] Under the French Protectorate, migration to France was a viable option for middle and upper class Jews. Social pressure from inside France, pre-existing diplomatic ties, and financial resources all contributed to this trend.

[vii] See Morocco Since 1830: A History, C.R. Pennell

[viii] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html#8

[ix] http://www.jewishagency.org/society-and-politics/content/36566

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco, Haim Zafrani

[xii] http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/features/codename-operation-mural-1.235412

[xiii][xiii] https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Jewish%20exodus%20from%20Arab%20and%20Muslim%20countries&item_type=topic

[xiv] The A to Z of Zionism, Rafael Medoff and Chaim I. Waxman

[xv] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html#8

References:

“Geography: Migration Trends.” Bitesize: BBC Radio. BBC, 1 Jan. 2014. Web. 1 Apr. http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/migration/migration_tren ds_rev2.shtml.

- Malka, Jeff. “June the 7th and the 8th 1948: Riots in Oujda and Jérada (Morocco).” Sephardic Geneology. 1 Jan. 2007. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. http://www.sephardicgen.com/databases/oujdaDjeradaSrchFrm.html.

- Medoff, Rafael, and Chaim Waxman. The A to Z of Zionsim. Metuchen: Scarecrow, Print.

- Pennel, C.R. Morocco Since 1830: A History. New York: NYU, 2001. Print.

- Sheleg, Yair. “Codename: Operation Mural.” Haartez17 Dec. 2007. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/features/codename-operation-mural-235412

- “The Virtual Jewish World: Morocco.” Jewish Virtual Library. Encyclopedia — Judaica, 1 2008. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Morocco.html#8

- Zafrani, Haim. Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco. Jersey City: Ktav House, Print.

Moroccan Jewish handicrafts