Feb. 24 marked the 79th anniversary of a Holocaust-era tragedy in which nearly 800 Jewish refugees from Axis-allied Romania lost their lives in the Black Sea. Their ship, the Struma, exploded in 1942 following an ill-fated attempt to reach Mandatory Palestine after they were not permitted entry into Turkey, which was then ruled by the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

As Europe’s Jews were being systematically annihilated during the Holocaust, thousands desperately tried to escape the Nazis and reach their ancient homeland, Israel, which was then part of the British Mandate of Palestine.

During one of these attempts, Jewish refugees planned to travel to Istanbul by ship, apply for visas there and then set sail to Palestine. Scholar Corry Guttstadt describes in her book Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust the events that led to the Struma catastrophe:

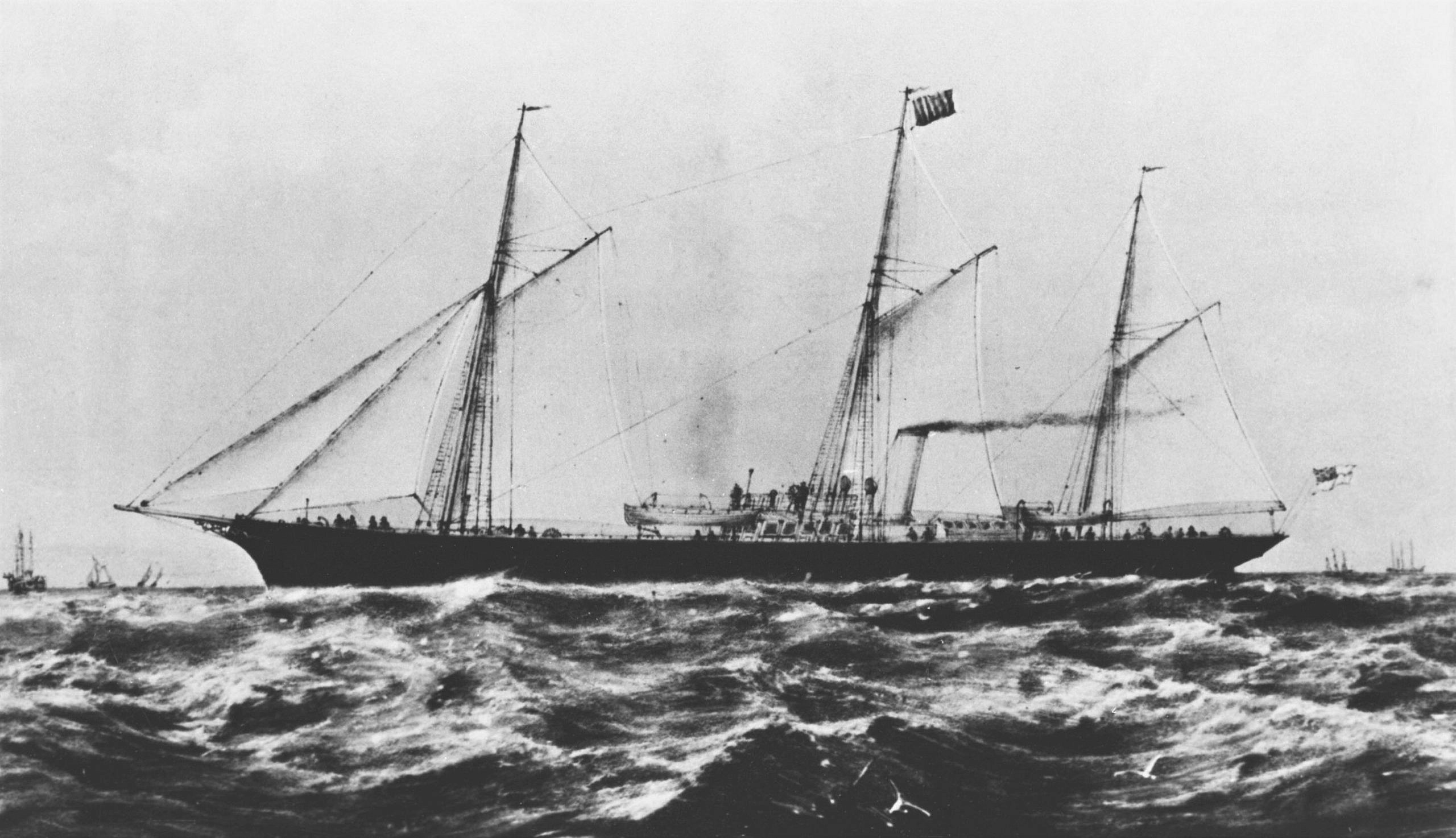

“The Struma was a Romanian passenger streamer sailing under the Panamanian flag that reached Istanbul on December 15, 1941, with 769 Jewish refugees on board. Not only was the ship completely overloaded but it was also not seaworthy because of a detective engine. For seventy days over the winter months of 1941-1942, the Struma sat in the Bosporus. Every day, the inhabitants of Istanbul could see the banner ‘Save Us’ that was fastened to the ship. Although Jewish organizations offered to assume all costs for housing the destitute passengers, they were forbidden to go ashore. Only a few people received special permission. The Turkish authorities hid behind the British position since the refugees did not have Palestine Certificates. After several weeks of anxious waiting, on February 24, 1942, the Turkish coast guard forced the Struma to leave Turkish coastal waters. While massive police forces had entered the ship in order to prevent any resistance of the passengers, the anchor chain was cut and the hapless vessel, without a working engine, was towed onto the open seas. The news that Great Britain had granted the children and youths on board the Struma entry to Palestine the day before came too late.

“The Turkish press had called the passengers of the Struma ‘uninvited guests’ (Vatan) and victims of ‘greedy ship brokers.’ Only one telegram by the state agency Anadolu Ajansi informed the Turkish press that work was stopped in Palestine for two days and commemorative services were held in memory of the Struma dead. The sole newspaper that picked up the news report was Ulus, in its edition for March 12, 1942. This led to a debate in the Turkish parliament on April 20, 1942, that focused not on the events themselves but on the alleged Jewish propaganda against Turkey. Some MPs remarked indignantly that ‘foreign foulers of their own nest’ had ensconced themselves at Anadolu Ajansi. Prime Minister Refik Saydam declared with regard to the sinking of the Struma, ‘Turkey cannot become the home of those who are not wanted by anyone else.’ ”

Ishak Alaton, a well-known Turkish-Jewish businessman who passed away in 2016, was 15 years old when the Struma reached Istanbul. He was one of the many members of Istanbul’s Jewish community to help the passengers and carried food to the ship. As Alaton recalled:

“The ship was not allowed to be moored to the dock; they [authorities] wanted to keep it [in the sea]. Supplies sufficient for 770 people and barges were taken [by the Jewish community] to the ship. I would arrive in the evenings and help to unload the sacks that were taken there by trucks. The [Turkish] Red Crescent only provided a showpiece aid. The real aid was organized by the elders and notables of the Jewish community living in Istanbul. My father Hayim Alaton was in that committee; he actually strove [to help the passengers]. For two months, the food, bread, and supplies needed for the survival of the passengers arrived in trucks. I still remember the smell of the bread today. Because we made a deal with the bakery and hot bread from ovens was put in sacks. [Businessman] Vehbi Koç saved four people from the ship. However, it was not covered by newspapers much. There was already censorship. There was no free press.”

Alaton said that Struma’s engine was taken to a shipyard in the Golden Horn to be repaired, but the ropes on which the anchors were tied were cut after an order from the government in Ankara without notice to anyone. “That is, 770 people were left to die by the government of the time,” added Alaton.

Peter A. Aldea’s maternal grandfather, Paul Fainaru Iacobovici, was one of the victims of the Struma catastrophe.

“Forcing 790 people to share a decrepit boat without beds or sanitary facilities in January/February weather was heartless,” Aldea told JNS. “We treat animals better. To then pull the disabled Struma boat into sea at the end of February and leave those people to die was criminal.

“In August 2000, the Russian submarine KURSK and its 188 sailors sank in the Barents Sea. The whole world watched and offered its help and wishes for the sailors and the Russians refused all international help and covered up the facts. Where was anything resembling help and compassion 58 years earlier? Where were the outcries and indignation? The Jewish community offered to take the Struma refugees in and be responsible for them but Turkish authorities refused.

“My grandfather was a kind, gentle, and generous man who was first and foremost a devoted family man who was adored by all his family. In addition to speaking Romanian, He was fluent in French and Turkish and was an avid reader. His wife, Fani Ludaici Iacobovici (1899-1986), never remarried. She helped her girls, Blanche and Annie, become professionals. She then helped raise all her three grandsons and lived to see them graduate from professional schools. She passed away in 1986 and is buried in Paris.

“My grandfather was educated in Izmir (Smyrna), was a Turkophile and did not deserve the death he received at the hands of the Turks.

“Redemption, however, begins with remorse and education. The Germans have done it as have the Japanese. To begin to make amends, the Turks should publicize the story of the Struma and their less than honorable role in it.”

Alaton, who was a witness to the Struma’s fate in the Sea of Marmara, also voiced similar sentiments in an interview in 2012:

“Someone from Ankara or from the party that was in charge of the government at the time should come out and apologize. It is time. We want to hear the sentence ‘I’m sorry.’ Turkey should show the courage to apologize and if it can do that, it will be purified, exalted and respected. We need to learn to apologize, and we should comprehend the virtue [of apologizing]. We need to reconcile with our past, and this must be our greatest goal.”

Turkey, however, has not recognized, apologized for or given reparations for any such incidents in its history. Sadly, given the current government’s ongoing hostility and aggression towards non-Turkish communities inside and outside of the country, it does not seem likely that Turkey will come to terms with its past in the near future. But until it honestly faces its crimes and secures justice for its victims, it will not be a truly civilized country.

Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. She is currently a research student at the MA Woodman-Scheller Israel Studies International Program of the Ben-Gurion University in Israel.