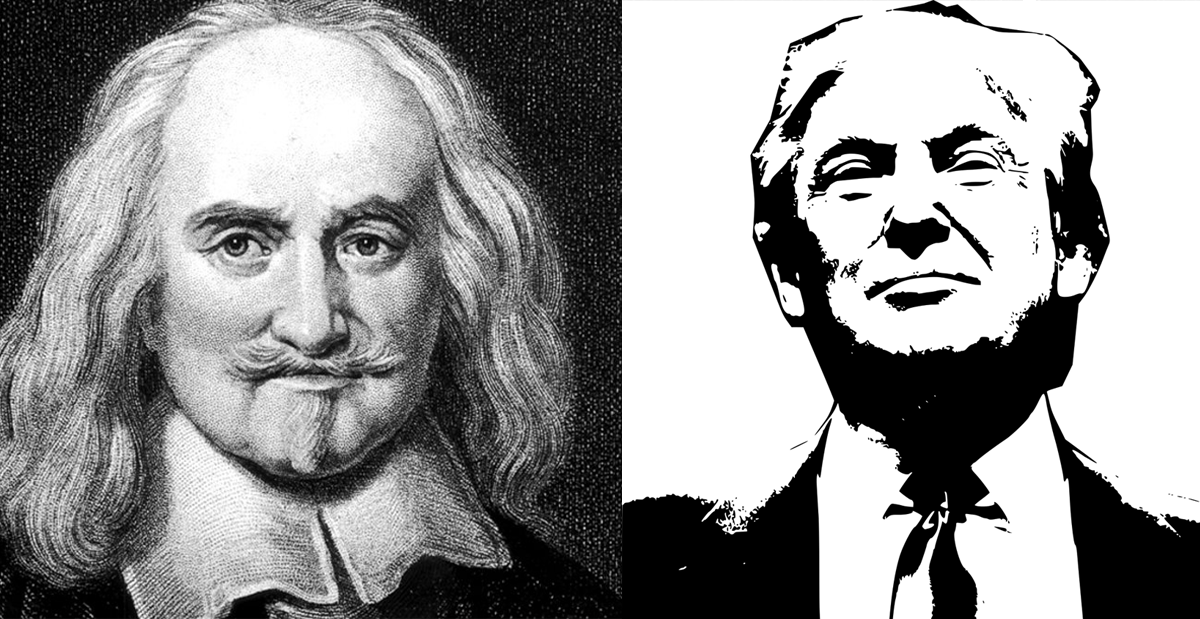

In the 17th century, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes famously warned against growing conditions of anarchy in world politics, conditions that he associated with a devastating “war of all against all.” Appearing in Leviathan, this prescient warning underscored the perpetual interdependence of all states and peoples, and served as a useful reminder to both scholars and policymakers that seeking national security at the expense of others must inevitably prove futile. Ironically, in view of the current US president’s conspicuously retrograde movement toward “America First,” the Hobbesian assessment was already recognized and favored by the Founding Fathers of the American republic.

Donald Trump’s corrosive ideas about “America First” are demonstrably false and inherently baneful. Accordingly, Mr. Trump ought to also soon be reminded of the French philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s cautionary observation that “no element can move and grow except with and by all the others with itself.”

In essence, “America First” needs to be discarded, immediately. Correspondingly, the alternative presidential posture must starkly reject any long-failed zero-sum orientations to international conflict. Countless conflicts — from World War II to recent events in Syria — quickly show us that events that start elsewhere and don’t “concern” America usually grow to concern and threaten us. Even more concretely, such imperative rejections of “America First” must be soundly based upon the prudent calculation that no nation-state should expect to survive at the expense of other nation-states.

It’s all quite plain. “America First” expresses an illusion that is sorely misconceived and prospectively lethal. If left unchallenged, it will support an injuriously atavistic mantra, one that would harden the hearts of America’s most recalcitrant adversaries. What is desperately required now is an abundantly broadened acknowledgment of human interdependence and interconnectedness.

World politics has always been shaped by continuously shifting balances in power, and by certain related correlates of war, terror, and genocide. To be sure, hope should still exist, but now, it should sing softly, unobtrusively, and in a decisively prudent undertone. Now, though obviously counter-intuitive, the optimal moment for celebrating science, modernization, entrepreneurship, technology, and a ubiquitous social media is mostly past.

Merely to survive on this imperiled planet, all of us, together, must finally seek to rediscover an individual life, one that is consciously detached from any patterned conformance, cheap entertainments, shallow optimism, or disingenuously contrived expressions of American tribal happiness. At a minimum, such survival will demand a prompt retreat from what Donald Trump has so mindlessly termed “America First.”

It’s not complicated. Learning from history, we Americans may yet learn something from “America First” that is both useful and redemptive. We may learn, for example, even during this national declension of Trump, that a commonly felt agony is more important than astrophysics; that a ubiquitous mortality is more consequential than any transient financial “success”; and that shared human tears may generally reveal much more deeply consequential meanings and opportunities than “everyone for himself” tax reductions or porously imbecilic border walls.

In The Decline of the West, first published during World War I, Oswald Spengler asked: “Can a desperate faith in knowledge free us from the nightmare of the grand questions?” This remains a vital query, one that will assuredly never be raised in our universities, on Wall Street, or absolutely anywhere in the Trump White House. Still, we may learn something productive about these “grand questions” by more closely studying American responsibilities in world politics.

Then we might finally understand that the most suffocating insecurities of life on earth can never be undone by further militarizing global economics, building larger missiles, abrogating international treaties, or replacing one abundantly sordid foreign regime with another.

In the end, moreover, even in our insistently squalid American politics, truth must be exculpatory. In what amounts to a promising paradox, “America First” can express a lie that can help us see the truth. This primal truth, moreover, is not all that complicated: What is required, above all else, is a genuinely wider consciousness of unity and relatedness on earth.