Ongoing Russian crimes against Ukraine are egregious and overlapping. Most conspicuous of these crimes are Vladimir Putin’s acts of aggression and of genocide. Jurisprudentially, even if Putin lacks any confirmable “intent to destroy” specific Ukrainian populations, Russia’s law-breaking behavior would still rise to the level of other relevant criteria or standards. Most recognizable, in this regard, would be Putin’s forcible deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia.

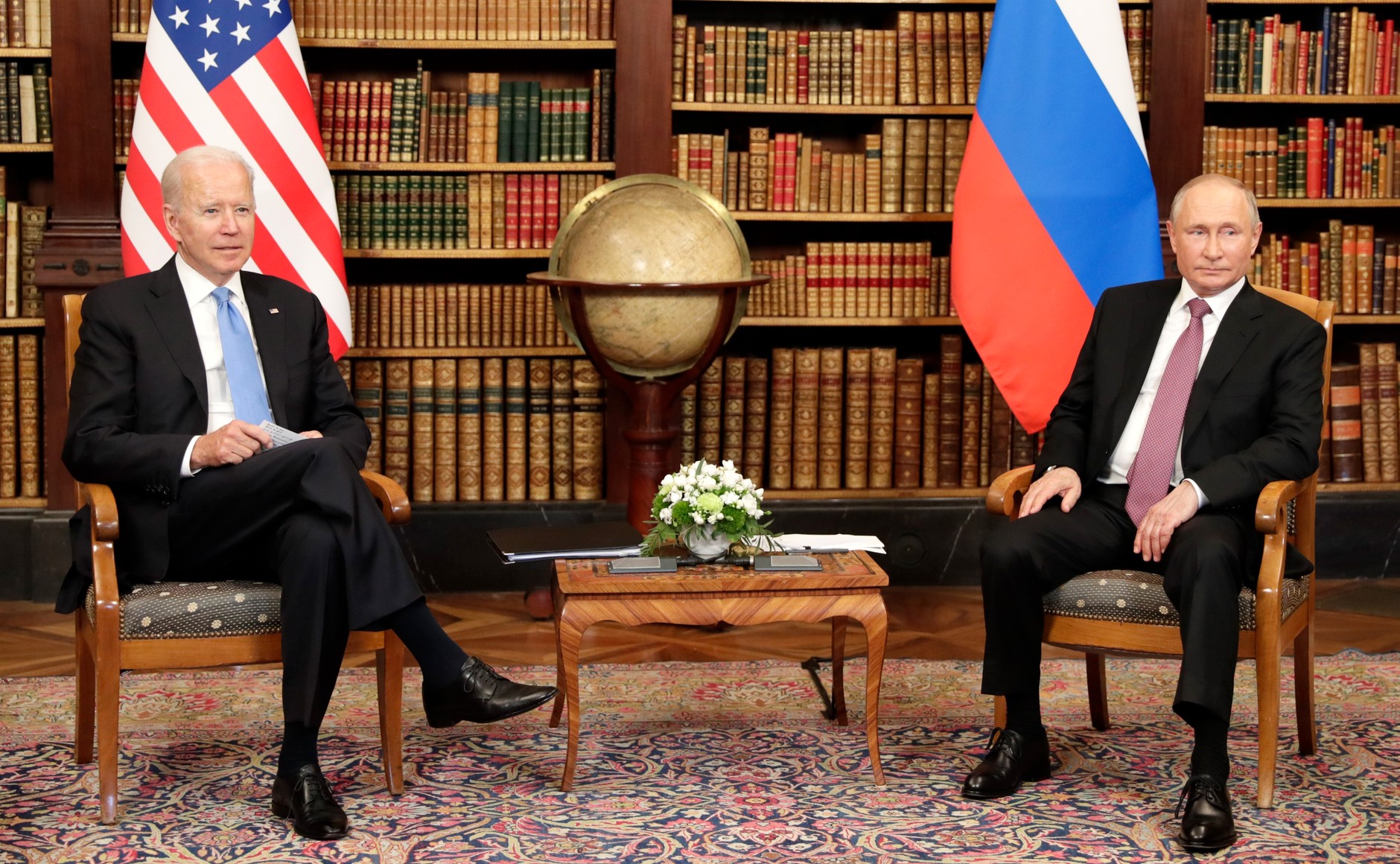

What are United States obligations in this “peremptory” matter? Inter alia, these obligations can never be permissibly disregarded. Among pertinent considerations, attempts by Washington to modify or halt Putin’s lawbreaking in Ukraine could also increase the odds of a superpower nuclear confrontation. How then, a basic query surfaces, should the United States do what is needed against Russia’s genocide in Ukraine without simultaneously encouraging a superpower nuclear crisis?

Significantly, this decisional dilemma is sui generis, or without precedent. In essence, there exist no tangible guidelines to answer such a potentially existential question with precision or reliability. In any event, leaving aside complicating particulars, American decision-makers must take explicit note of the two relevant concerns (nuclear war and genocide) and assess the risks of each concern. In the end, these decisions will concern comparative hazards, including variously subtle ways in which nuclear war risks and genocide risks could impact each other.

For the United States, international law enforcement is never just a volitional matter. Because such enforcement has been “incorporated” into the law of the United States (see Article VI of the US Constitution and two key cases from the US Supreme Court: Paquete Habana, 1900 and Tel Oren versus Libyan Arab Republic, 1984), it would support variously binding expectations of American domestic law.

There is more. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) obliges signatories not only to avoid committing genocide themselves, but also to oppose and prevent genocidal behavior committed by other states. At Article III of this Convention, the obligation extends to grave acts involving “conspiracy to commit genocide,” “attempt to commit genocide,” and “complicity in genocide.” Such core expectations are known formally in law as “peremptory” or “jus cogens” rules. This signifies rules or obligations that permit “no derogation.”

There is more. These obligations are discoverable in corollary and complementary expressions of international law, both customary and codified. More specifically, even if a transgressor state were not a party to the Genocide Convention, it would still be bound by customary law and (per Art 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice) by “the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations.”

Neither international law nor US law advises any particular penalties or sanctions for states that choose not to prevent or punish genocide committed by others. But all states, most notably “major powers” belonging to the UN Security Council, are bound by “peremptory obligation” defined at Article 26 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. This is the always fundamental legal requirement to act in continuous “good faith.”

The “good faith” or Pacta sunt servanda obligation is derived from an even more basic norm of world law. Known commonly as “mutual assistance,” this civilizing norm was famously identified within the interstices of classical jurisprudence by eighteenth-century legal scholar, Emmerich de Vattel. Later, it was reaffirmed by William Blackstone, whose meticulously assembled Commentaries on the Laws of England became the bedrock of United States law.

As a historic aside, Vattel, whose The Law of Nations was first published in 1758, became a favored jurisprudential source of Thomas Jefferson. In fact, this American founding father relied upon his brilliant Swiss antecedent for many key principles he later chose to include in the Declaration of Independence. As a present-day matter, a prospectively revealing question should arise: How many American citizens can imagine an American president reading classical political philosophy or international law?

It’s a silly question, even after Donald J. Trump’s inglorious departure.

Back to Ukraine. In the strictest sense, though the United States could never be held accountable under law for any legal abandonment of the Ukrainian people, any willful failure to act against Putin in this arena of ongoing Russian criminality would violate general and immutable principles of international law. This anti-genocide regime includes the London Charter of August 8, 1945; UN Charter (1945); Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-Operation Among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (1970); Affirmation of the Principles of International Law Recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal (1946, 1950); and the International Law Commission (ILC) Articles on State Responsibility (2001).

In its landmark judgment of 26 February 2007 “Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro), the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that all Contracting Parties have a direct obligation to “prevent genocide.” Somewhat counter-intuitively, the ICJ found it easier to acknowledge this obligation expressis verbis (“with clarity”) than by referencing the corollary legal requirement not to commit genocide themselves.

Much earlier, sixteenth-century Florentine philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli fused Aristotle’s plans for a more scientific study of world politics with assorted cynical assumptions about geopolitics. His best-known conclusion focuses on the palpably timeless dilemma of practicing goodness in an evil world: “A man who wishes to make a profession of goodness in everything,” Machiavelli asserts in The Prince, “must necessarily come to grief among so many who are not good.”

If taken too literally, however, this conspicuously cynical assessment could lead not only individuals but also entire nations toward a primal “state of nature.” Among other things, this retrograde trajectory would describe a condition of rampant anarchy and disorder, one best clarified by another classic political philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. In his Leviathan (a work similarly well-known to Thomas Jefferson), life in this “every man for himself” condition is grievously harsh. Such a corrosively sad individual life, we may learn from the seventeenth-century Englishman, must be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

What Hobbes was unable to foresee were the devastating consequences of any future exacerbations of anarchy by nuclear weapons.

Gabriela Mistral, the Chilean poet who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945, wrote that crimes against humanity carry within themselves “a moral judgment over an evil in which every feeling man and woman concurs.” Today, continuing to coexist with other states in a self-help or vigilante system of international law, the United States should do whatever is legally possible to publicize and impede Russia’s genocide or genocide-like crimes against Ukraine, but do so without expanding the likelihood of superpower nuclear confrontations. In this daunting dual-level obligation, though there would exist no “ready to use” policy guidelines, critical national policy choices will still have to be made.

Origins will be important. The core origins of both war and genocide lie not in monstrous individual persons (we know this from authoritative scholarly exegeses of the Holocaust and certain other genocides), but in collectivities, in whole societies that effectively loathe the individual. In such societies, as we may learn especially from such “existential” thinkers as Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Ortega y’ Gassett, Hesse and Jung, the “mass” becomes more tangibly “omnivorous” and further inclines the now voracious state toward murderous foreign policies.

As long as powerful states are driven by “mass,” they will regard themselves, per nineteenth-century German philosopher Hegel, as the “march of God in the world.” With such a fundamentally distorted view, these states can become, as Nietzsche explains in Zarathustra, “…the coldest of all cold monsters.” Plainly, such intolerable transformations could include variously palpable inclinations toward war and genocide.

In the 21st century, for some of these states, a war in such circumstances could become nuclear. Should this happen, antecedent legal issues of an American policy balance between nuclear war avoidance and genocide prevention would immediately become moot. This is because nuclear war and genocide will no longer represent discrete or separate perils.

Now, nuclear war itself will have become the de facto instrument or creator of genocide.