Former California Gov. Gray Davis, a liberal Democrat, and the Koch Brothers, billionaire businessmen and Libertarians often associated with conservative causes, would seem to have little in common. However, that is why digging into one’s ancestry can be unsettling, even alarming. Davis’s grandfather, William Rhodes Davis, and the Koch Brothers’ father, Fred Koch, were business allies in a deal that provided cheap Mexican oil to Adolf Hitler’s Germany during the 1930s. After Mexico nationalized its oil industry, Grandpa Davis made a deal with Lázaro Cárdenas to purchase Mexican oil at below-market prices to be shipped to the Eurotank facility in Hamburg, Germany, which Fred Koch’s company, Winkler-Koch Engineering of Kansas, converted into an oil refinery. The refined oil then was sold to the German Navy.

According to author Bradley W. Hart, an assistant professor at California State University, Grandpa Davis also wanted to purchase surplus cotton from U.S. federal warehouses which he planned to sell directly to Germany. Whereas profits from the Eurotank facility were required to remain in Germany, cotton sales could provide Grandpa Davis with hard cash that he could use in other parts of the world. To be able to obtain the surplus cotton, Grandpa Davis needed friends in high U.S. government places and so began a program of making large campaign contributions to the Democratic party. However, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration was not interested in the United States being an indirect supplier of cotton goods to Nazi Germany, so it nixed the cotton deal. After Germany invaded Poland, thus beginning World War II, Grandpa Davis met with the Nazis’ Air Marshal Hermann Göring, proposing to him that Germany accept Roosevelt as a neutral peace arbiter. When he brought the idea back to Roosevelt and Adolf Berle, the assistant secretary of state who was considered an expert in counter-intelligence, FDR told him that while the idea sounded interesting, nothing could be done unless he received a formal proposal from some government – a proposal that never came. Meanwhile, the administration ordered the FBI to put Grandpa Davis under surveillance.

His plans dashed, Grandpa Davis decided his next best course of action would be to defeat Roosevelt politically. He successfully obtained $5 million from Göring to back a candidate of either party who might be able to defeat Roosevelt in 1940. He had in mind John L. Lewis, the head of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO of the AFL-CIO), who was no friend of the president’s. However, when Roosevelt formally announced for a third term, there was no support for Lewis among Democrats. Meanwhile, to Davis’s chagrin, the Republicans nominated Wendell Wilkie, who like Roosevelt was an internationalist, not an isolationist. Nevertheless, Willkie seemed better to Davis than Roosevelt, so he paid $55,000 of the Nazis’ money for a national radio hook-up in which Lewis denounced Roosevelt, and called for the Republican nominee’s election. Davis subsequently became affiliated with the American First Committee, whose most famous advocate was aviator Charles Lindbergh. Davis died before Pearl Harbor, and his company, W.R. Davis, Inc., attempting to rehabilitate its image announced a gift of 5,000 barrels of oil to Great Britain. That didn’t stop the U.S. government from filing a $38 million suit against Grandpa Davis’s estate, but only $850,000 was finally realized.

Grandpa Davis’s son, Joseph Graham Davis, moved to California, and his son Joseph Graham Davis Jr., better known by the nickname “Gray” Davis, served as Gov. Jerry Brown’s chief of staff in the 1970’s, then went on to be elected in turn to the state Assembly, state controller, lieutenant governor, and in 1998 governor. Ironically, in a recall election, he was ousted by actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who had overcome in the campaign the news that his Austrian father had been a minor Nazi official. Another irony, not mentioned in Hart’s book, was that Davis’s chief of staff in the gubernatorial office was former Congresswoman Lynn Schenk, daughter of a Holocaust survivor, who has been a prominent and passionate supporter of the Jewish community. Governor Davis, according to Hart, “never knew his controversial grandfather, who had died before he was born, and was estranged from the alcoholic father who abandoned the family in the early 1960s.”

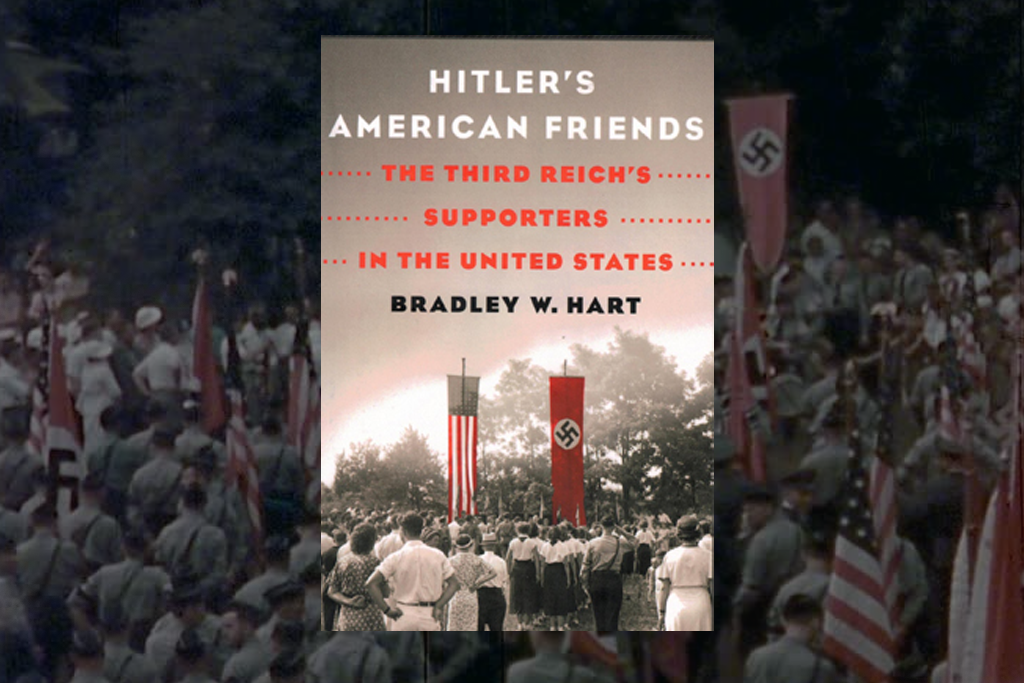

The tale of William Rhodes Davis is just one of many surprising stories in this well-researched book, which tells of such other of Hitler’s American supporters and inadvertent allies as Lindbergh; Fritz Julius Kuhn, the leader of the German American Bund; William Dudley Pelley, leader of the Silver Shirts; the radio priest, Father Charles E. Coughlin; radio’s Protestant evangelist Gerald Burton Winrod; America Firster Gerald L.K. Smith; U.S. Senator Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota (whose speeches often were written by Nazi agent George Sylvester Viereck); Senators Burton K. Wheeler of Montana and Rush Holt of West Virginia; U.S. Rep. Hamilton Fish III of New York; automobile magnate Henry Ford; General Motors Overseas Operations President James D. Mooney; Mooney’s second-in-command Graeme Howard; and writer Elizabeth Dilling, among a host of others. Anti-Semitism characterized most, if not all, of these Hitler friends, although their demands that America stay out of Europe’s war typically was gift-wrapped in the cause of U.S. patriotism.

I believe that this book is valuable, not simply because it reveals a little remembered chapter of American history, but also because it shows how vulnerable the United States is to foreign efforts to subvert American democracy. The pro-Nazi element’s failure to keep America neutral fortunately was defeated by a combination of factors; in the first place by the competition and egotism of the various leaders, who were unable or unwilling to work with each other; in the second place by the watchdog efforts of Congressman Martin Dies’ investigating committee and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and most importantly by Japanese imperialism, which pulled America into the World War with the advent of the Dec. 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World