“Cursed is Hitler, cursed is Mussolini … Blessed is Roosevelt, blessed is Churchill.”

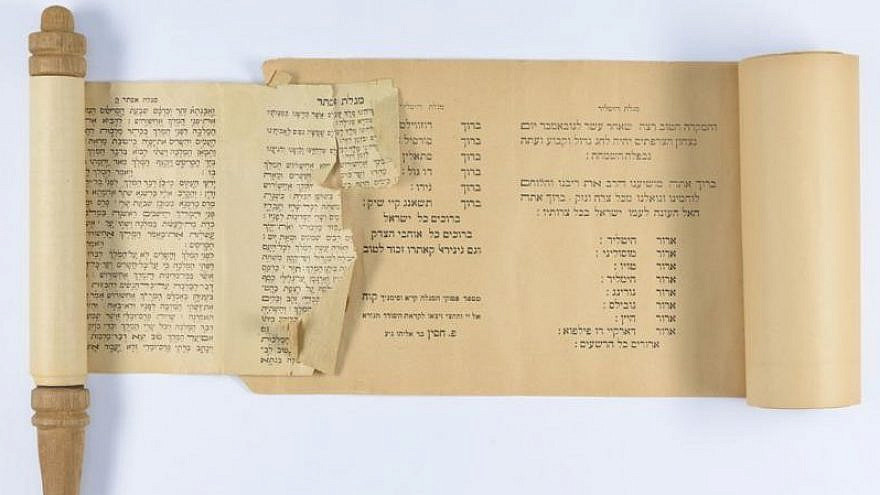

With these words, the Moroccan scribe Prosper Hassine concluded his account of World War II and the Holocaust. The story was familiar, but what made Hassine’s work unique was its style: Written on a long parchment scroll, it adopts the format, phrasing and cadences of the Megillat Esther, the Scroll of Esther—the biblical story of the near annihilation of Persian Jews in the fifth century BCE. In the absence of a Jewish queen to avert the Axis’s evil decree, Hassine called his work “Megillat Hitler.”

Purim Hitler was part of a long tradition. Beginning in the Middle Ages, Jewish communities in the Diaspora established special Purims—complete with their own Megillah readings, feasts and edible gifts—to celebrate their deliverance from persecution and disaster. Individuals were also known to establish their own Purims. In 1731, David Brandeis and his family were imprisoned in Bohemia when a gentile died after eating some jam sold in their grocery store. The day when Brandeis was exonerated (it turns out it was tuberculosis, not food poisoning) was celebrated by the family as Purim Providl, “Plum Jam Purim.”

Today, most of these special Purims have been consigned to the dustbin of Jewish history trivia. But the tradition has not died out entirely. After a brush with death on a Los Angeles freeway in 2007, author and artist Sonia Levitin decided to establish her own personal Purim. “Profound experiences, especially those that prompt gratitude, should be kept in your mind and in your actions,” says Levitin, a Holocaust survivor.

Indeed, special Purims that weave together memory, gratitude and celebration are worth remembering, not least for the insight they provide about the holiday that inspired them.

This year, the holiday begins at sundown on Monday, March 6 and continues through the evening of Tuesday, March 7.

Purim is uniquely a holiday of Jewish life in the Diaspora, says Wendy Zierler, a rabbi and a professor of modern Jewish literature and feminist studies at Hebrew Union College‒Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City: “Esther is the story of the Jews; it’s the only book in the Bible that makes such widespread use of the words ‘Yehudi’ and ‘Yehudim.’ It is a story about the necessity of Jewish power as a form of group protection, of lobbying, rallying, activism and sticking one’s neck out for one’s fellow Jew.”

‘The only positive instance of women’s writing in the Bible’

Some special Purims reflected this emphasis on Jewish participation and self-protection. More often, however, the stories told in special Megillot describe miraculous deliverance from harm. In the late 1300s, the community of Syracuse was accustomed to greeting the Sicilian king holding Torah scrolls in their arms as a mark of respect. When a converted Jew informed the king that the Torah cases were actually empty—the Jews kept the real scrolls safely tucked away in their synagogues—the entire community was threatened with extermination. A timely visit from Elijah the prophet averted disaster, and “Purim Saragossa” (as Syracuse was sometimes called then) was born.

But even when the salvation was supernatural, the establishment of special Purims themselves expressed the independent spirit of their mother holiday. Zierler points out that much of the action in the Scroll of Esther takes place via writing. Decrees are issued and rescinded; Mordechai and Esther both proclaim the holiday of Purim by writ: “the only positive instance of women’s writing in the Bible,” she says.

Establishing their own prayers and customs, in addition to writing their own Megillot, allowed Diaspora Jews to master circumstances that were often beyond their control and to claim some part of their experiences as their own.

‘We all have redemptive experiences’

Purim has another quality that makes it an obvious choice for adaptation: The Scroll of Esther itself records that the residents of the Persian capital Shushan should celebrate the holiday a day after everyone else—Shushan Purim—because that was when they experienced it.

To this day, in walled cities such as Jerusalem, Shushan Purim is celebrated one day later.

It was this openness to experience and personal memory that drew Levitin to the holiday. After turning the wrong way into oncoming traffic on the 405 Freeway in Los Angeles—“I was sure I was going to die”—Levitin says the traffic inexplicably slowed, and she managed to pull off onto a side street: “I just sat there shaking and thinking, God must know who I am. He must know my name.”

Levitin duly wrote down her experience and has observed her “Freeway Purim” ever since by hosting a yearly dinner.

After telling her own story, she often finds herself listening to her friends describe their own miraculous escapes. “I believe we all have redemptive experiences,” she says. “One of the reasons Jews are still around and unified, as we are, are the memories we keep intact and celebrate every year.”

But perhaps more than any other quality, it was the spirit of the Purim story with its many drinking parties (nine in all!) and its dramatic reversals of fortune that made it an attractive choice for Jews seeking respite from a state of constant instability and peril.

“It’s a story that shows the Jewish sense of humor, which has always helped us in times of trouble,” notes Zierler. “The whole book is meant to provoke a big, rollicking laugh.”