Two months ago, on Nov. 7, 2021, one of the Shi’ite militias in Iraq deployed a suicide drone against the home of Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi. The drone exploded, wounding a few security guards, but Kadhimi himself lived. Immediately after the incident, a delegation of high-ranking Iranian officials, led by commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force, Maj. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, landed in Baghdad. They wanted to calm things down, but also to investigate the incident. The militia that dispatched the drone operates under Iran’s auspices and is funded by Tehran, but in this case had acted on its own, with no explicit instructions—even going against Iranian policy.

In the West, people thought Iran was playing dumb and had actually ordered the attack, despite its denials. It turned out, however, that Iran was just as surprised by the incident as the Iraqi government. Even Washington—which cannot be accused of any fondness for the IRGC or the Shi’ite militias in Iraq—made it clear that Iran wasn’t behind the attack. High-ranking officials in Israel confirmed that last week.

Soleimani was the most important military official in Iran. His rank belied his seniority—officially, he was a major general, one of many in the IRGC, but practically speaking he was far above them. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, saw Soleimani as a son.

‘Nasrallah barely knew’

Soleimani was one of the most notable figures of the Islamic Revolution, and many stories were told of his heroism. Soleimani encouraged these myths, especially in his final years, after emerging from the shadows. He began allowing his picture to be taken and granting interviews, becoming a celebrity. It’s possible that this prompted him to become careless, ultimately costing him his life. Experts think that if he hadn’t been killed, he would have gone into politics.

“Khamenei believed in Soleimani and trusted him,” said Meir Javdenfar, an expert on Iran and a senior researcher at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy, and Strategy at Reichman University. “Under [former Iranian President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad, who betrayed the supreme leader after he was elected president, Soleimani was always loyal to him [Khamenei].”

Soleimani had carte blanche from Khamenei. According to IDF Brig. Gen. (res.) Dror Shalom, former head of the research division in the IDF Military Intelligence Directorate, Soleimani would carry out actions and tell Khamenei only after the fact.

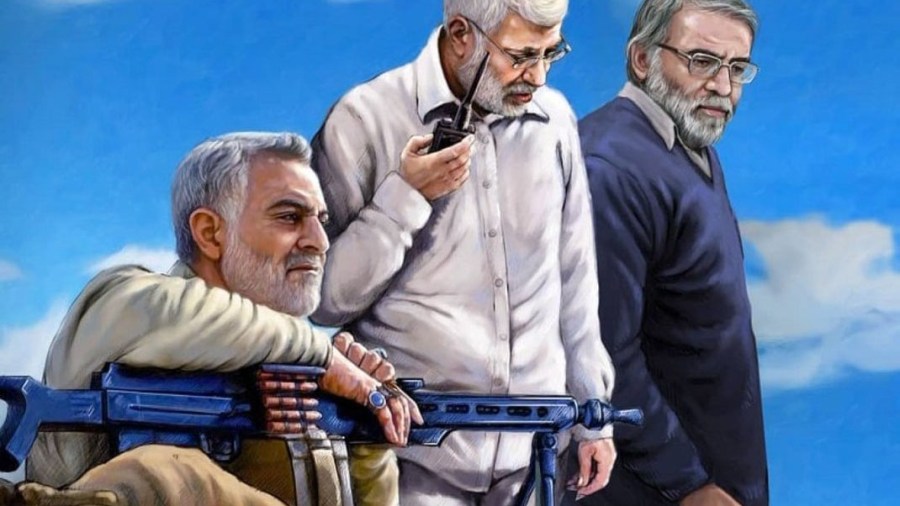

“Everyone understood that he was acting on behalf of the leader and speaking in his name. He knew how to take Khamenei’s strategy and turn it into an operation. Just like Mohsen Fakhrizadeh [Iran’s top nuclear scientist, who was killed in 2020] in the field of nuclear research. They were two exceptional, key figures, and it’s not a coincidence that they’re no longer alive,” said Shalom.

When Soleimani first took command of the Quds Force at the end of the 1990s, it was a relatively small organization that mainly concerned itself with carrying out terrorist attacks all over the world. The first major operation Soleimani oversaw was in Afghanistan. Later, the Quds Force became active in Iraq and in Lebanon, and after the Arab Spring of 2011, in Syria. He had branches in all these countries.

In Lebanon, his deputy was Imad Mughniyeh, in Syria, it was Brig. Gen. Mohammed Suleiman. Mughniyeh, the admired Hezbollah leader, was killed in Damascus in 2008 in an action attributed to the Mossad and the United States. Suleiman was killed approximately six months later by a sniper while at home in the Syrian city Tartus, an action also attributed to Israel.

The targeted killings of both these commanders forced Soleimani to tighten his connections with Syrian President Bashar Assad and Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. He became a kind of mentor to Assad—later saving his life and keeping him in power by lending all the force of the IRGC and its proxy Hezbollah to Assad’s war against the Syrian opposition forces until the latter were defeated (due in part to aid from Russia, and bolstered by the U.S.-led coalition forces’ war against the Islamic State.)

Soleimani’s relationship with Nasrallah was more complicated, but no less close.

“Nasrallah was more cautious than he [Soleimani] was, because he remembered his experience with Israel in 2006. He didn’t always like what Soleimani was doing, for fear he would complicate things for Lebanon, but he didn’t stop him,” noted a high-ranking Israeli security official.

Soleimani led the efforts to outfit Hezbollah with rockets and precision missiles that could be aimed to within 10 meters (33 feet) of any point in Israel. This project was his exclusive initiative—”Nasrallah barely knew about it, and wasn’t really interested,” the official added. “Soleimani was behind it and pushing for it.”

The Quds Forces’s efforts to shore up Hezbollah have been one of its two main projects in recent years, and has been a major target of airstrikes in Syria attributed to Israel. The second campaign Soleimani spearheaded was to secure an Iranian presence in Syria.

“In 2016 we pointed out that Soleimani would change his strategy from saving Assad to entrenching [Iran] in Syria,” said Shalom. “We thought he would identify an opportunity to turn Syria into a platform of resistance against Israel. We spotted that vision even before Soleimani fully conceived it, and we prepared for it. When he came up with it, we were already deep into the ‘between-wars’ campaign and were able to thwart it,” he explained.

Hajizadeh is aiming for the stars

Soleimani’s idea was simple. Because he didn’t want to involve Hezbollah and Lebanon in a war, but still wanted to launch regular attacks against Israel, he planned to set up permanent bases in Syria and populate them with thousands of Shi’ite fighters he would train, fund and equip, who would then make life tough for Israel.

Israel’s determination torpedoed the plan. Hundreds of actions, large and small, were launched to keep Iran from positioning itself to attack. Military facilities were targeted before they were built, weapons and supply convoys were bombed and psychological operations were launched. Nevertheless, Soleimani continued to pursue his vision. A few times, he tried to respond with attacks on Israel (such as launching drones armed with rockets, mostly toward the Golan Heights), but without success. The low tactical capabilities of the pro-Iranian forces in Syria, combined with Israel’s intelligence and operational superiority, made it possible to thwart all the attempted attacks.

“Soleimani wanted to surround us with a crescent of terrorism,” said the Israeli official. “With some of his plans he failed, but his general idea didn’t collapse. The opposite.” This refers mainly to the process that began near the end of Soleimani’s life, which has gathered speed since he was killed: flooding the region with precision strike capabilities, mostly UAVs armed with various weapons systems, that allow Iran to use its proxies to attack, avoiding responsibility and risk.

Capabilities like these, that have a range of 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles), have already been delivered to the Houthis in Yemen and some of the militias in Iraq, and we can assume that similar systems are already in Lebanon and Syria, as well. Iran, of course, also has them in its own territory, and has used them to attack Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facility in September 2019, a massive strike that caused enormous damage. Iran denied any connection to the incident, but there is solid intelligence that the missiles were fired from Iran itself.

The man responsible for the Aramco strike was Brig. Gen. Amir Ali Hajizadeh, commander of the IRGC’s Aerospace Force. Hajizadeh was one of the main beneficiaries of Soleimani’s death. His own status has increased dramatically in the last two years, and he is now involved in areas that used to be exclusively handled by the Quds Force. IRGC Commander Hossein Salami has also gained considerable power since Soleimani has been out of the picture.

“Soleimani wouldn’t have allowed this to happen,” said the Israeli defense official. “He wouldn’t have let the guy eat away at the Quds Force’s authorities. He was very zealous about making sure that what took place outside Iran’s borders was his responsibility and under his orders. That’s no longer the case, and it’s not certain that it’s good for us. The new players have tools and resources, as well as a lot of motivation. They could cause us some real headaches.”

Soleimani’s successor, Ghaani, is very different.

“He’s bland, uncharismatic, a kind of office functionary,” said Shalom. “At first, there were a lot of people on the Shi’ite axis who doubted his ability to do the job, and he’s still having a hard time delivering the goods.”

Proof of this can be seen in the recent dismissal of commander of the Quds Force in Syria, Joad Rafari, after his grandiose plans failed to bear fruit, in part because of Israeli preemptive actions.

“Ghaani is not Soleimani, but it would be a mistake to compare him to who Soleimani was in the last 10 years of his life,” said Raz Tzimmt, an expert on Iran from the Institute for National Security Studies. “He should be compared to what the Quds Force was before that: a small, secret force. We tend to attribute too much of the Quds Force’s difficulties to targeted killings, but the truth is that’s not the only factor. The wars in Syria and Iraq are over and these countries are undergoing processes of reorder, and in Iraq and Lebanon there’s criticism of the Iranians over the Quds Force’s activities, which is making things complicated for them.”

Still, Tzimmt said, Ghaani is facing a number of difficulties that stem from the large shoes he was forced to fill.

“Soleimani wasn’t just a notable military strategist, but also a super politician,” he said. “Ghaani has much less influence in the region, over Hezbollah and Nasrallah, for example, than his predecessor did. But we shouldn’t get our hopes up here, either—Nasrallah still sees Khamenei and Iran as the source of his religious authority, and that’s not likely to change. It has more influence on the other militias, like the ones in Iraq, because they’re more strongly rooted in personal loyalty to Soleimani, who assembled and led them.”

Under Soleimani, the Quds Force underwent two major changes. It transformed from a small-scale, secret unit to an enormous organization operating in several countries. At its peak, some say the Quds Force paid salaries to 150,000 soldiers. The second change was in its influence—Soleimani made the Quds Force into the dominant factor in the IRGC, and outside its ranks as well. His exceptional military abilities—both in terms of strategic vision and getting down to practical brass tacks—combined with his personal charisma and the vast influence he had as part of the supreme leader’s inner circle channeled a great deal of power into the organization he led.

According to the Israeli official, “There aren’t a lot of people who can make changes like that, to take a relatively small organization and make it into a super-operator with systems in several countries at once. Soleimani did it in Iraq, Syria and in Yemen, all while pushing to strengthen Hezbollah.”

Ghaani is continuing to carry out the same vision. The big wars are over, but Iran keeps on keeping on. Anyone who thought it would draw back, because of Israeli airstrikes, U.S. sanctions or certain restrictions from Russia, will turn out to have been mistaken. And that is exactly Israel’s claim—that the activity in Syria is just part of a much broader strategic campaign needed to reduce Iran’s regional influence and stop it from growing stronger.

“Iran is a deep strategic challenge, far beyond its nuclear program,” said Shalom. “Dealing with it is [for Israel] like the west dealing with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.”

Shalom believes that it was critical to take out Soleimani, because he was the rare kind of leader for whom it is hard to find a replacement. He thinks that Iran’s rather ineffectual reaction to his death had to do with the fact that the United States was behind the strike. If Israel had been responsible, Iran would have responded much more harshly, he said.

But in the past two years, American deterrence has been eroded, mostly because former President Donald Trump has been replaced by Joe Biden, who is leading a policy line that leans much more toward appeasement. The result is clear–it can be seen in the Iranians’ audacity in the Vienna nuclear talks and in attacks on Iraqi bases hosting American forces. Even Israel could pay for America losing its deterrence.

This past year, Iran has waged a maritime campaign against civilian vessels owned by Israelis as a counterbalance to strikes on oil tankers and military ships under Iranian control that were attributed to the Israeli Navy. It’s doubtful we’ve seen the last move by Iran; senior defense officials said last week that a recent series of airstrikes—including two major ones on the Latakia port in Syria—attributed to Israel will likely not go unanswered by Iran.

If Soleimani were still alive, he would certainly push for heavy retaliation, and that’s likely what Ghaani will do, as well. With Soleimani or without him, Iran goes on, on all fronts, with all its might. Its revolutionary spirit and imperialist aspirations ensure that the front against Iran and its proxies will stay hot.

This article first appeared in Israel Hayom.