In order to bring the world of Amid Falling Walls to the stage, Folksbiene enlisted the talent of the multi-faceted media production company Winikur Productions to secure imagery from Jewish cultural life immediately before, during, and right after the Holocaust. Winikur Productions has deep experience working with difficult content, particularly the Holocaust, as they’ve collaborated on projects for The Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, the Nancy and David Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center, and the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, among others. But Folkbiene was not looking for the kind of imagery most associated with the Holocaust—Amid Falling Walls would need visuals that showed the vibrant cultural life that endured against the odds.

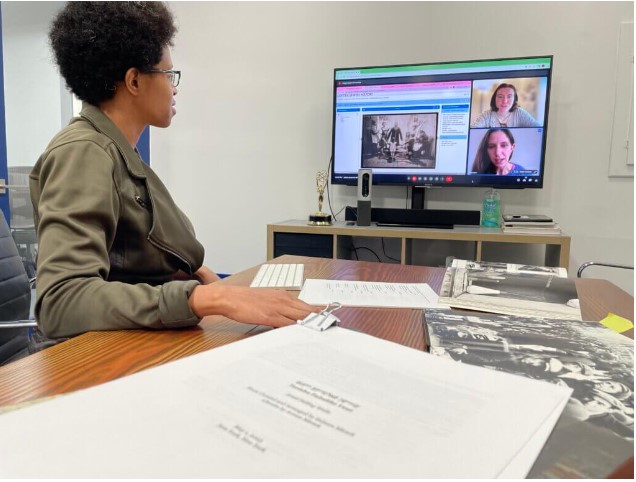

We sat down with two members of Winikur Productions’ Amid Falling Walls research and story-telling team—Julia Kahn, project manager, and Abigail Hendrix, associate producer—to learn more about what it takes to create the background visuals that contextualize the music and performances of Folksbiene’s forthcoming musical.

What is your role in bringing Amid Falling Walls to the stage?

We are handling all of the image research and licensing for Amid Falling Walls. Avram Mlotek, Zalmen Mlotek, and Motl Didner have tasked us with finding—and securing the licensing for—photos, video, and materials that provide context for and help to illustrate the performance. This may include footage of cabaret and theater performances, audience photos, and anything else that transports the audience back to the setting of the musical. We find the images and then consult with the creative team and ask: Does this image help you tell the story? Throughout the process, we endeavor to find the exact images to fit the story. Once the creative team makes a decision on the footage, we work on getting licensing from the archives and sometimes from the families or individuals who donated the items to an archive.

So much of what we see from the Holocaust is the horrific imagery of suffering and death, but that’s not what Folksbiene was looking for. How did you go about finding imagery for these different aspects of that time?

When we begin a project, we first go to the archives we’ve worked with in the past. We know the archivists there and we’ve learned how to navigate their systems, so it’s the most logical place to start. We quickly learned, however, that we would need to expand our search because the images we sought were much harder to find. For 15 years, we’d been researching Holocaust materials and we thought we knew what was out there, but this project has pushed us to discover new sources that have revealed so much more material. We found new archives, met new archivists, and learned how to use their systems to conduct research in their collections. These organizations are constantly scanning newly acquired materials. As the amount of material expands, new stories are revealed.

Pictured are Yerachmiel Wolfberg and Yitzhak Borstein.

What are some of the challenges you’ve faced doing this work?

Each archive has its own rules for how to search, as well as its own organizational practices, so working in new archives presents an initial challenge. This is where it can be incredibly important to work with talented archivists who know their collections well. For this project, a lot of what we were looking for was in personal collections; for example, a family has donated all of the papers, photos, and items they’ve found from a deceased loved one. Many of these collections are not yet keyword searchable, so it’s painstaking work to comb through page by page, item by item. Going through these collections is akin to doing an analog search digitally— it’s like being handed a box of someone’s items, knowing basic information about them and where they lived, and searching until you find what you’re looking for (or not). Collections might have a brief description (e.g., theater programs, letters from Warsaw), but you still need to go through all of it. Another challenge is that these materials are in multiple languages and scripts, and it’s here that we rely on Folksbiene. Overall, the work is 99 percent interesting and fun and one percent frustrating (with some tail-chasing). It’s a game of patience and persistence: we know from the start that it’s going to take a long time—and it still usually takes even longer than expected—but the end result is always worth it.

How is this work different from other work you’ve done related to the Holocaust?

Doing any research related to the Holocaust is very difficult—you see terrible images of the worst things that have happened. From the very first list of requests we received from Folksbiene, we saw this would be different. The creative team was asking for images that showed the vibrancy and vitality of life during that time. And, it was a relief to find visual evidence of that: artists and poets in theatrical, visual, and written acts of resistance. In the photos of theatrical performances, you could see that the sets and costumes were made under pressing circumstances, and that was a testament to the way they used the arts to celebrate and preserve their culture and also to hold out against its destruction. Even in the darkest moments, they were declaring: we are here!

Integral to the team, but unavailable for the interview, is Zalika Corbett, technology officer.