Between July 29 and Aug. 5, some 2,000 scholars and enthusiasts of Esperanto—the 136-year-old artificial language with Jewish roots—are expected to descend on Turin in northern Italy.

The World Esperanto Association (UEA), which has held a conference every year since 1905, except during the world wars, will host its 108th Congress at the Polytechnic University of Turin. And as it notes on its website, interpreters are unnecessary, as participants come to speak Esperanto.

The association has members in more than 120 countries and estimates—based on sales of textbooks and local society memberships—that “the number of people with some knowledge of Esperanto is in the hundreds of thousands and possibly millions.”

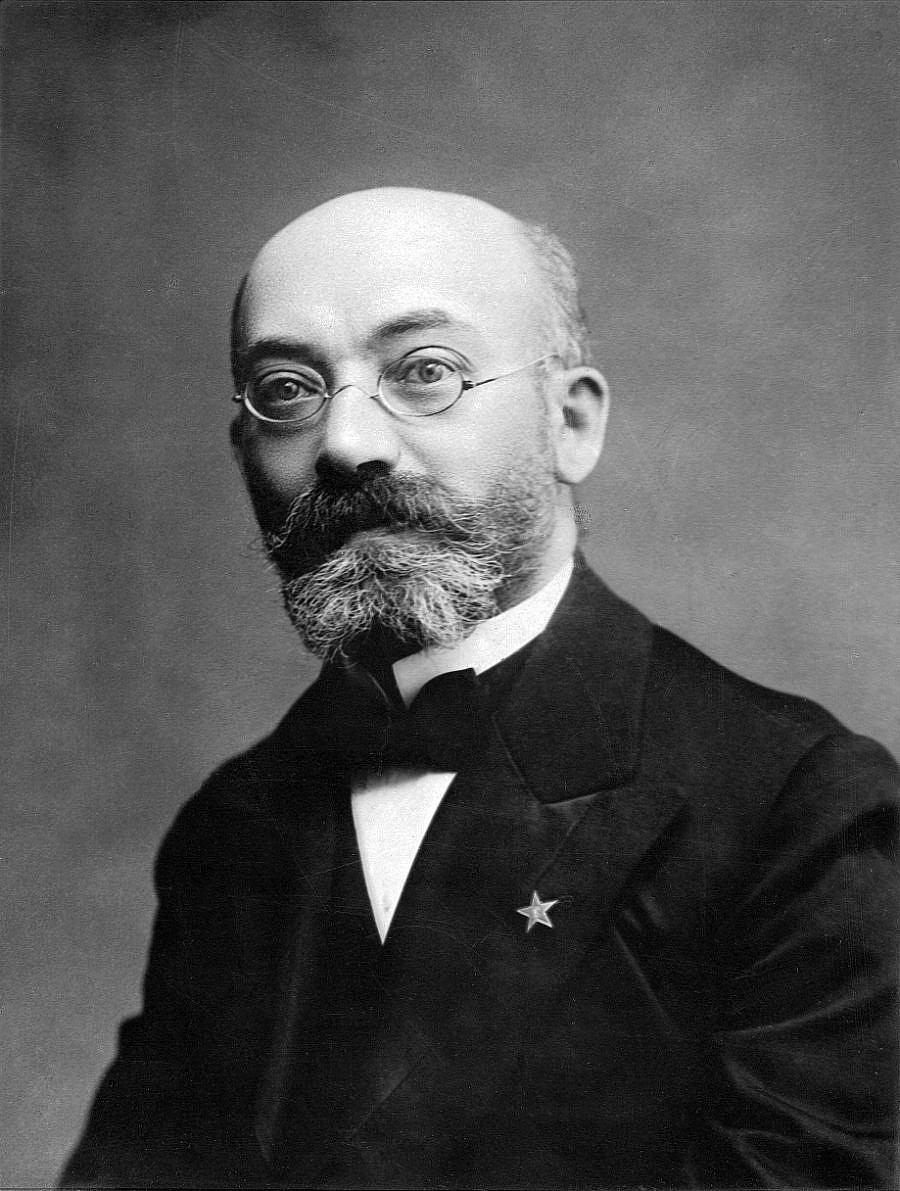

The language dates back to 1887, when Polish ophthalmologist L.L. Zamenhof, who was Jewish, created Esperanto as a second language to be used internationally. Earlier in the decade, he tried to standardize Yiddish. (The root of the word Esperanto means “hope.”)

“It’s not clear exactly when Zamenhof gave up his Yiddish project. Still, the palimpsest of Yiddish in Esperanto remains clear: it was Yiddish, a mongrel of Germanic, Semitic, and Slavic words, that modeled for Zamenhof an international language,” wrote Esther Schor, an English professor at Princeton University, on the Yiddish Book Center website.

“What had happened to Yiddish over a millennium, in mass migrations of Jews from Western to Eastern Europe and back, Zamenhof would make happen to Esperanto—but at his writing desk, and in just a few years,” she added.

Zamenhof planned Esperanto to have simple grammar for ease of learning.

Born alongside modern Hebrew

Esperanto arose at a time when Europe was plagued by antisemitism and pogroms.

“Esperanto was born in the same era that the modern Hebrew revival was,” Amri Wandel, a senior astrophysicist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and vice president of the World Esperanto Association, told JNS. “Some Jews opted for Hebrew, while others went for Esperanto.”

Many Esperanto speakers appreciate that the language’s founder was Jewish, and an estimated 100 speakers can be found in Israel, where they host weekly meetings, according to Wandel, who learned Esperanto 50 years ago.

When he began studying the language, he met Holocaust survivors who had learned it in Europe, he said. More recently, Wandel has added terms from his field to the language, including praeksplodo or “Big Bang.” (The best-known Esperanto word is probably mirinda, which means “amazing” and is also the name of a soft drink, which PepsiCo distributes.)

The ‘most successful’ artificial language

Paul Frommer, clinical business communication professor emeritus at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business, is a linguist who created the Na’vi language for James Cameron’s 2009 film “Avatar.”

“Esperanto is by far the most successful of all artificial languages,” he told JNS.

Frommer, who does not speak Esperanto, thinks that its success shows that “well-constructed” languages can function as natural languages do.

“Creating a language is much more than simply coming up with a list of words,” he said. “It is a complicated process.” The language creator must design sounds and forge sentence structure rules, he said.

Some 2,000 people speak Esperanto as a first language, Wandel told JNS. (George Soros has been said to be a native Esperanto speaker, although that has been disputed.) Frommer told JNS he finds it inspiring that so many people speak the artificial language as a first language.

Esperanto has been spoken in the 2004 film “Blade: Trinity,” and it appears in some of the signs in the 1940 silent Charlie Chaplin film “The Great Dictator.” The latter film parodied Nazi Germany.

Adolf Hitler condemned Esperanto in Mein Kampf, seeing it as connected to a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world. Zamenhof (1959-1917) had three children, all of whom were murdered in the Holocaust.

The founder’s great-granddaughter, Dr. Margaret Zaleski-Zamenhof, told JNS that she remains active in the Esperanto community and plans to attend the Congress and “represent the family.”

After the war, the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin also targeted Esperanto. Ayatollah Khomeini initially urged Iranians to learn Esperanto after the Revolution, but he appeared to lose interest in it as he found that the Baha’i faith embraced it.

Esperanto appears poised to make further inroads in Africa, however. Next year, the congress will be held in Tanzania—the first time it will come to the African continent.

“This is a big step for the language and the growth of the community after so many years,” Alessandro Amerio, of the congress’ organizing committee, told JNS.

Wandel told JNS that the language will continue to evolve.

“While Zamenhof’s dream of making Esperanto a universal language has not become a reality, its legacy lives on through the active community,” he said.