The last thing most American Jews needed was another excuse to skip synagogue. But after the shootings in Pittsburgh and Poway within the last year, many members of the Jewish community are worried about going to services since they think that doing so could place them in danger.

Part of that is understandable.

What happened at the Tree of Life*Or L’Simcha Congregation in Pittsburgh and Chabad of Poway in Southern California was a frightening reminder of the way the virus of anti-Semitism continues to spread across the globe, even in the United States. And in a country like America, where mass shootings have become a shockingly regular feature of life, it’s hardly surprising that some of those mentally disturbed and/or Jew-hating white supremacists that have been guilty of these crimes would seek to target Jewish institutions. The threat of violence is real, not imaginary, and it would be foolish to ignore it.

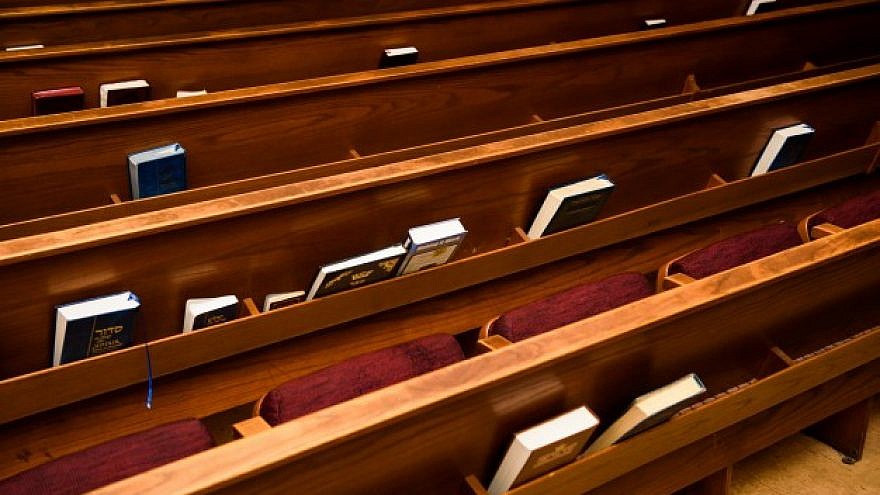

But there is an unfortunate by-product of the entirely commendable efforts of Jewish organizations to speak up about both the anti-Semitic threat and the need for greater security at synagogues, as well as at other Jewish sites. The problem is that after so much talk about rising anti-American anti-Semitism, some of us have been so frightened that they may be convinced that the discretion is the better of valor and will stay away from synagogue, even on the High Holidays, which are the two or three days a year when most Jews normally show up.

Despite the attempt to weaponize the threat of anti-Semitism from far-right sources for partisan profit and to unfairly implicate President Donald Trump in this problem, the truth is that support for such anti-Semitic crimes is completely marginal. The overwhelming majority of Americans deplores anti-Semitism and attacks on Jews, who, truth be told, are not alone or isolated. To the contrary, the overwhelming reaction to Pittsburgh and Poway demonstrated as much as any other indicator that Jews remain fully accepted in American society in a way that is unprecedented in the history of the Diaspora. Those who are hyping the real problem of contemporary anti-Semitism into an existential crisis for the future of American Jewry are not helping the community.

Still, there’s also no denying that the atmosphere of fear these incidents have fed plays into the already diminishing appeal of synagogues to the approximately 90 percent of Jews who identify with the non-Orthodox denominations or none at all. According to Gallup, only about 50 percent of American Jews are affiliated with a synagogue of any kind. According to a more detailed survey conducted by the Pew Research Institute, these numbers continue to trend downward—a reflection not only of declining religious affiliation for Americans as a whole, but particularly for a Jewish population that is increasingly assimilated and less attracted to traditional institutions like synagogues.

Throw in the idea that going to synagogue on a day when crackpot extremists know that there will be large numbers of Jews in attendance and you’ve given some people the idea that staying away is the way to avoid trouble.

But this is exactly the wrong response to hate.

Just as was the case in the days after Pittsburgh, when large numbers of Jews and non-Jews gathered to express their solidarity with the victims and their defiance of the haters, so, too, must we do our best to ensure that the first High Holidays after the two shootings will show that Jews are undaunted even by these tragedies.

Synagogues have their problems in an aging community, and for generations, they have been losing members in much of the country. Some of this is an inevitable product of shifting demographics, and some of it is a function of the inability of some institutions to meet the needs of younger generations. No matter the issue, it’s important for Jews to show up and be counted this year. The best way to fight anti-Semitism is to let the haters—be they on the right or the left—know can’t win.

This is also a challenge for rabbis who look to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur as their best opportunity to address full rooms of congregants. And with some of the denominations joining the political war on Trump, the temptation for some leaders to use their High Holiday sermons to engage in political advocacy, even if it is accompanied with weasel-worded claims of nonpartisan motivations, especially in those with largely liberal memberships, will be great.

And that, too, is a mistake.

What we need more than ever from our rabbis this year is an effort to bring us together, rather than rhetoric aimed at tearing us and the nation apart.

This Rosh Hashanah, Jews need to stand up to hate by being present, and rabbis need to use the Days of Awe to remind us of our obligation to examine our own shortcomings before decrying the alleged failings of our neighbors and politicians. If we are to effectively combat hate, as well as help our nation at a critical time, then we must focus on the ability to listen, learn and try to bind our wounds, rather than making them worse.