Following revelations that the U.N.’s Palestinian refugee agency UNRWA colluded with Hamas in Gaza, 12 countries have withdrawn or paused their funding to the agency at time of writing, with more likely to come. However, there is little discussion as to why an agency set up as a temporary measure to aid refugees from Israel’s 1948 War of Independence should still be giving relief to the descendants of Arab refugees 75 years later.

Interestingly, it is not generally known that UNRWA was actually established to help refugees on both sides of the conflict—both Arab and Jewish. Initially, UNRWA defined those for whom it was responsible as “a needy person who, as a result of the war in Palestine, has lost his home and his means of livelihood.”

This definition included some 17,000 Jews who had lived in areas of then-Palestine conquered by Arab forces during the 1948 war and around 50,000 Arabs living within Israel’s armistice frontiers. Israel took responsibility for these individuals and by 1950 they were removed from the UNRWA rolls. This left some 550,000 Palestinian Arabs—according to a New York Times estimate in Dec. 1948—under UNRWA’s authority.

At the time, there was no internationally recognized definition of what constituted a refugee. In 1951, the U.N. Refugee Convention agreed on the following definition:

A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

This definition certainly applies to the 850,000 Jewish refugees who fled persecution in Arab countries after 1948 and mostly made their way to Israel. Returning to those countries would have and still does put their lives at risk.

The burden of rehabilitating and resettling the 650,000 of these refugees who arrived in Israel was shouldered by the Jewish Agency and American Jewish relief organizations, such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Together with Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe, they were shunted into transit camps called ma’abarot in appalling conditions.

At the time, the American aid earmarked for Middle East refugees was supposed to have been split evenly between Israel and the Arab states, with each side receiving $50 million. The money to take in the Arab refugees was handed over to UNRWA, while the United States gave another $53 million for “technical cooperation” to the Arab countries. Thus, in effect, the Arab nations received double the money given to Israel even though Israel took in more refugees, a large number of whom had been expelled from Arab countries.

In 1951, a bill presented to Congress marked the first and last time that any mechanism was established to provide for these Jewish refugees. The total amount Congress allocated to Jewish and Arab Middle East refugees was equal to $1.5 billion today.

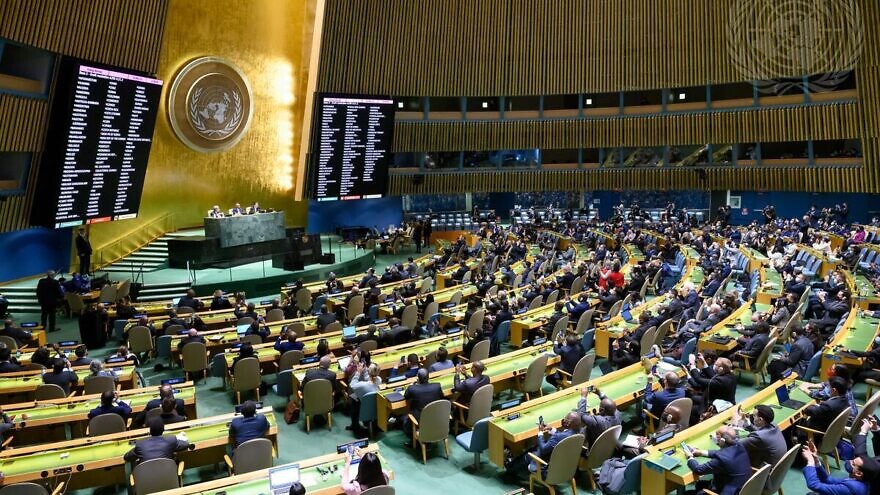

At an early stage in the Arab-Israeli conflict, the U.N. was coopted by its powerful Arab-Muslim voting bloc. This bloc engineered a shift from universal concern for refugees to an obsession with only one refugee population—the Palestinians. While UNRWA is dedicated to the exclusive care of Palestinian refugees, all other refugees in the world are served by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In fact, there are 10 U.N. agencies solely concerned with Palestinian refugees, most of whom are not refugees but rather descendants of refugees. These agencies define refugee status as depending only on “two years’ residence” in “Palestine.” The definition makes no mention of “fear of persecution” or resettlement.

Most tellingly, out of 65 million recognized refugees around the world, Palestinian refugees are the only ones permitted to pass their refugee status on to succeeding generations. As a result, it is estimated that the current population of Palestinian “refugees” is over five million, only a fraction of whom are refugees under any reasonable definition.

Moreover, alone among the refugees of the world, Palestinian refugees are granted the privilege of demanding “repatriation” over resettlement. Israel, for obvious reasons, considers this a red line.

Nonetheless, the Arab nations have maintained this double standard both as a weapon against Israel and to avoid the substantial cost of resettling the refugees themselves. In 1959, the Arab League passed resolution 1457, which stipulated that, except in Jordan, the Arab countries would not grant citizenship to applicants of Palestinian origin. This discrimination continues today.

In contrast to the billions of dollars that the international community has allocated to Palestinian refugees, no such aid has been earmarked for Jewish refugees. The exception was a $30,000 grant in 1957 that the U.N., fearing protests from its Muslim members, did not want to be publicized. The grant was eventually converted into a loan, which the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee paid back.

On only two occasions did the U.N. acknowledge that Jews fleeing a Middle East or North African country were bona fide refugees. In 1957, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, August Lindt, declared that the Jews of Egypt who were “unable or unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of the government of their nationality” fell within his remit. In July 1967, the UNHCR recognized Jews fleeing Libya as refugees under the UNHCR mandate.

Needless to say, none of these Jews still define themselves as refugees. Despite immense hardships, they are now full citizens of Israel and other countries.

Is it too much to ask for a similar humanitarian solution to the predicament of Palestinian refugees?