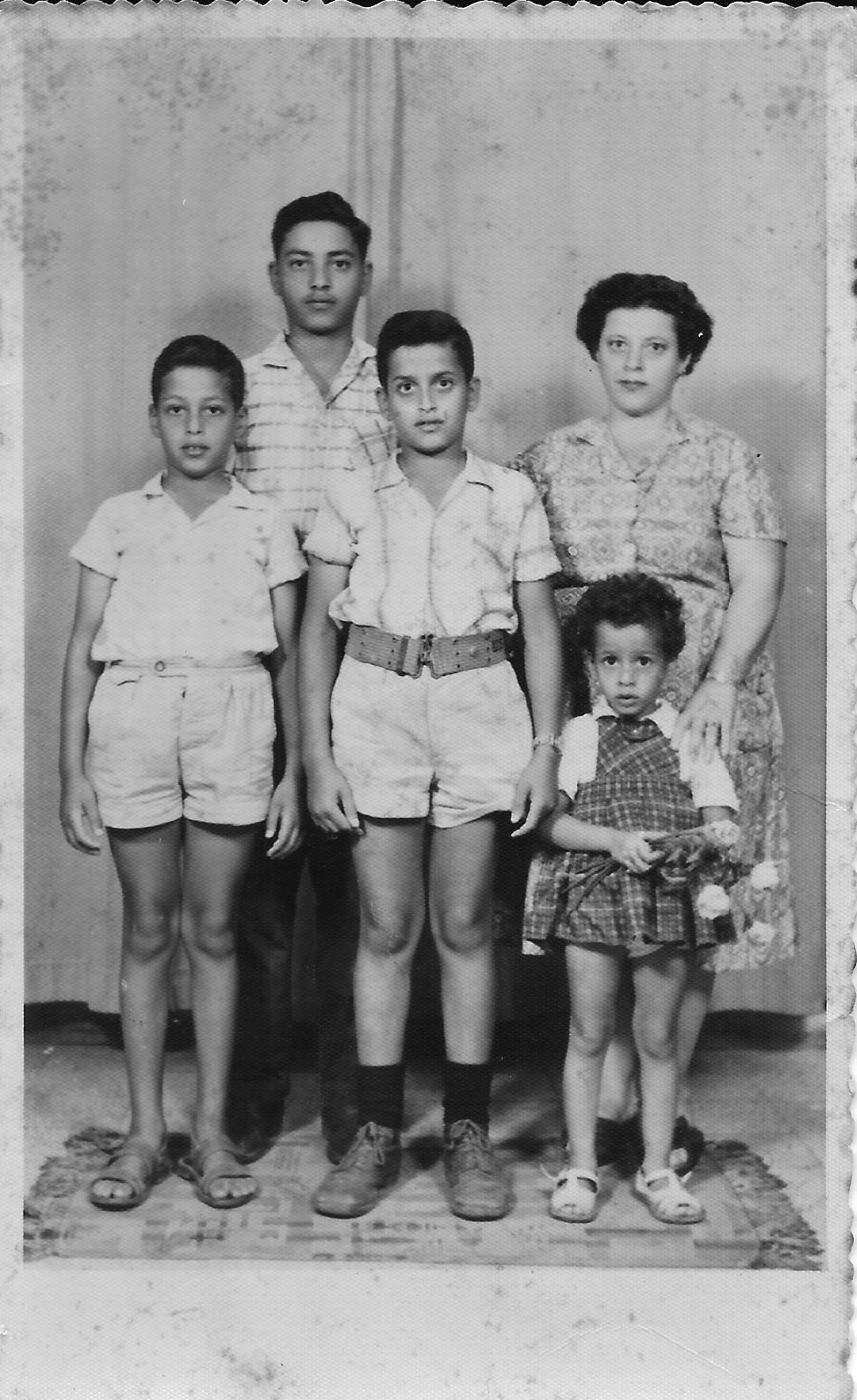

In March of 1956, Leah Zaki, 27, gave birth to her fourth child in Kfar Saba, Israel. The baby was the fourth boy in the family and weighed more than 7 pounds. In the five days he was at the hospital, the baby was breastfed and determined to be healthy. Just before Leah was to be released, a nurse came to take the infant, who had just been fed, for a final check-up. In less than a half-hour, the same nurse returned to notify Leah, my grandmother, that her child was dead. The cause was indeterminable, she said.

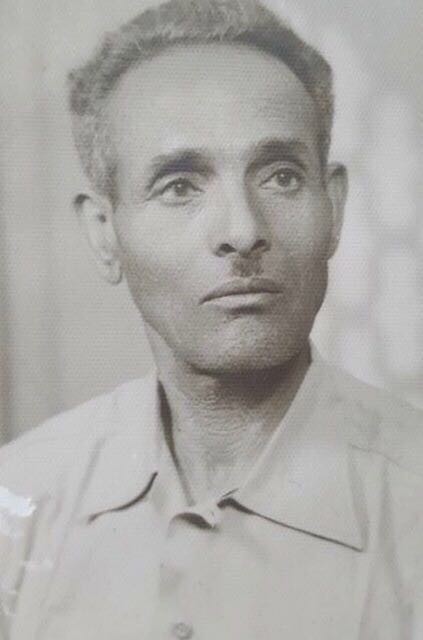

My grandmother and grandfather refused to leave the hospital without seeing a body. They begged, pleaded and wept. Hospital staff told them that police would come to arrest them if they didn’t leave. Eventually, fearful for their three children at home, they left. They felt that they had been mocked and humiliated, and robbed by the very country they had helped to build.

There was never even a death certificate issued (nor a birth certificate). I checked with an associate who works in the Misrad Hapnim, the Ministry of Interior Israel. I confirmed that there was no record of my grandmother even giving birth in 1956.

I started to gather anecdotal experiences I heard from other Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, including an aunt by marriage of Moroccan origin who had a brother she said was stolen. In Israel, I met with relatives around my late grandmother’s age who remembered her pregnant. They all confirmed that she had given birth to a healthy baby in 1956.

I knew my mother was telling the truth, but I didn’t want to believe it. A country that I love so much—that means so much to me—could not possibly have been involved in such a conspiracy to sell babies for profit or give them away.

True, many of the early Ashkenazic founders of Israel, even David Ben-Gurion himself, did not consider that Jews of the Orient had much of a culture or education. But could they have been part of a massive cover-up? Perhaps early players within the government were even involved?

Three separate inquiries have examined what the mainstream media in Israel has called the “Yemenite Children Affair” since a bulk of the families who have come forward are of Yemenite origin. My grandmother, however, was a Damascene Jew, and allegations of thefts of children have come from large segments of Middle Eastern Jewry in Israel. All of these government inquiries have concluded that the bulk of missing babies died of diseases, and that their parents were not involved or informed. Where those children were buried, however, remains a mystery, as there are also allegations that these purported graves are empty.

Occam’s razor tells us that when we are given competing hypothetical answers to a given issue, we should accept the one that makes the fewest assumptions. Perhaps these babies became sick and died because the country was so new, so poor and medicine was not readily available? So many babies becoming sick? And a disproportionate number of them boys? And why weren’t there clearly marked graves of deceased infants? Why weren’t parents shown bodies prior to alleged burial?

These are questions Israeli society continues to grapple with. To his credit, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu set out to “right an historic wrong.” In December 2016, the state of Israel declassified some 200,000 documents that claim to address the adoptions, often illegal, of babies of predominately Jewish immigrants from Yemen and the wider Arab world, according to families. The full archive is set to be available in 2066. What has been released so far is progress that has not been seen before on the issue. Yet so much more must be done.

Unfortunately, article after article in North American mainstream Jewish publications have often painted a story of mostly conspiracy-driven families who could not accept that their children were dead after three separate state commissions. The same stereotype is subconsciously perpetuated—that poor Middle Eastern Jews who lost their babies continue to cling to conspiracy theories. It’s a tough argument to swallow; a bunch of mostly Sephardic and Mizrahi religious nationalists who continue to build families in Israel are hardly the type to peddle conspiracy theories.

In Israel, it’s a different case altogether, as the issue receives considerably more attention from the media and politicians alike. It’s common knowledge and part of the pop-culture lexicon, even becoming the subject of memes.

In one such meme, for a page remembering childhood memories in Petah Tikva, the author satirizes a countrywide issue that has received considerable attention: “Remember when babies were sold in the Hasharon Hospital by weight?”

Indeed, it’s not conspiracy theorists or Israel-bashers who talk about the stolen babies in Israel. It’s concerned families and citizens.

Hours before her newborn was taken from her, my grandmother was asked if she had other children at home and whether they were boys. She never rested. My grandfather, until his dying die, would say that “they” stole his son.

My mother, since I was old enough to understand, explained that I had an uncle out there somewhere. She also told me that for years, she feared that she would inadvertently meet and marry her own brother. She was obsessed with knowing birthday and details of any man who ever showed interest—lest she happen to commit one of the gravest human sins. Her experience isn’t unique. At least hundreds of cases have been documented in which individuals have found their missing siblings. Most of the parents are now dead.

A film by Idit Ben Shimol features interviews with attorneys for the advocacy-based group that seeks to put pressure for greater transparency on the issue, Achim Vekayamim. In a portion of the film, lawyer Yael Nagar discusses the possible complicity of shipping company, Tsim, which transported stolen infants from Israel to the United States and Europe. Leah Frid’s father, Emil Malul, was a worker at the Port of Haifa. After being told to leave the port, he came down from his station and said he witnessed something strange. “He said, ‘I saw passenger ships, and nurses with a lot of babies in their hands getting on the passenger ships,’ ” his daughter explained. Frid also alleged that her father, bewildered, asked what was going and was told that the babies were gifts from David Ben-Gurion himself by a high-ranking port official.

“There was nothing here; there wasn’t even a country,” my great-aunt by marriage, Yafa Kalash, 93, explained about moving to the British-controlled Mandate from Damascus. “I remember when she gave birth,” she said of my grandmother and described visiting her at the hospital. “He was a very beautiful baby.”

Hundreds of testimonies, including from people who found their siblings through DNA testing, have been painstakingly documented. Some parents and siblings of stolen babies describe receiving mandatory military summons for children that had disappeared. Those who hadn’t had a chance to name their children didn’t even have a document to prove the child had ever come into this world, much like my family.

It’s a common refrain among Mizrahi families in Israel, and just about everyone seems to know a family that had a child or even two go missing. In some cases, families have left memorial candles at empty graves or phony burial records.

Instead of suggesting that these people (my family included) are conspiracy theorists or grief-ridden simpletons, it’s about time that international Jewry grasped the fact that countries have been involved in cover-ups like this one before—and demand some answers. We owe it to the families, many who have sacrificed sons and daughters in wars for Israel’s survival and security, to tell the truth and provide closure. We owe it to ourselves, too, as advocates of Israel to hold the country accountable if a massive cover-up did take place.

The gaping wound hasn’t even begun to heal, and the stain on the country’s history will become a source of greater embarrassment the longer officials stall. Waiting until 2066 for answers is simply inexcusable and crudely convenient, as it assures that the few who care will still be around.

Reut R. Cohen (@reutrcohen) is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer and journalism professor.