We begin with a scene from 60 Minutes: footage of a young woman lying on the ground being attended to by medical personnel alongside a scorched Israeli bus. This haunting scene is followed by Leslie Stahl interviewing “a big guy with a full head of hair that’s starting to turn gray.”

“The man is me, Stephen Flatow,” he writes more than 20 years later. “The young woman lying prone on the ground, being treated by medics, is my daughter Alisa. She was a 20-year-old college honor student at the time of the attack. The suicide bomber who set off the explosives, a so-called martyr, had unknowingly set off something else, too: a long battle between me—a New Jersey real estate lawyer—and the governments of both Iran and the United States. It would be a battle that I’d win, but a victory that could never compensate me for what I had lost.”

The fact that among the dead that day was this particular American college student who had the father she did was destined to change the law of her native country and fated to impact all other American victims of foreign terror forever.

But on that warm April day, in shock and living the grief of a parent who’s lost his beloved child, nothing in this father’s past could have prepared him for what lay ahead.

In these pages, he takes us along on his harrowing battle to achieve some degree of justice for his daughter.

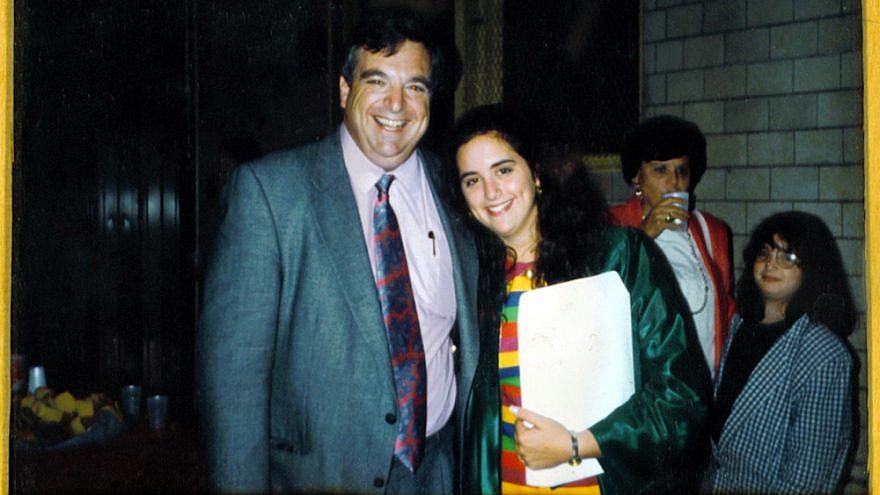

Not content with his tale of telling truth to power, Flatow also introduces us to Alisa, who, from the time she was a young child, knew her own mind and elevated her family to new heights. At 4, she calmly asked her father which school she was going to attend for kindergarten. “Alisa, you’re going to the Pleasantdale School,” he answered, alluding to the local public school.

“She looked at me and she looked at her mother. She told us—not angrily but calmly, as if simply stating a fact—‘No, I’m not. I’m going to a Jewish school with my friend Becky, and Mommy has to call Becky’s mommy tonight to find out about it because I’m not going to the Pleasantdale School.’ And with that she walked out of the room.”

Two days later, her parents were touring the Jewish school. As predicted, not only did Alisa attend, but all four of her siblings followed her into Jewish day schools.

Fast-forward 16 years and, after two-and-a-half years at Brandeis University, Alisa set out for Jerusalem to study at Nishmat, a women’s learning center. She was traveling on a bus with friends through Gaza when a terrorist detonated a bomb and exploding shrapnel hit her in the head.

Although Alisa wasn’t conscious when her father arrived at the Soroka Hospital in Beersheva, he got there in time to hold her hand, speak to her and kiss her. After consulting with his wife and rabbis conversant in Jewish medical law, this father said “yes” to donating his daughter’s kidneys, lungs and other organs to patients in Israel who needed them. With one dominant thought: “I know that the Mishnah, the first part of the Talmud, says that if a person saves one life in Israel, it’s as if he has saved the entire world.”

“Roz turned to me and she said, ‘You didn’t get the name of the hotel where she’ll be staying. What if something happens?’ For some reason I said, ‘Don’t worry. If something happens, we’ll know about it.’ Well, I was not wrong about that.”

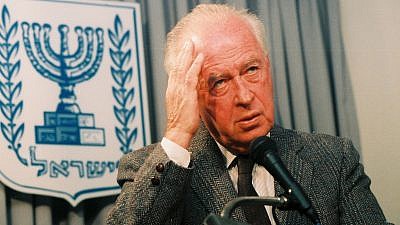

A month later, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin visited the Flatows in their New Jersey home, to thank them for the organ donations. “Today,” he told them, “her heart beats in Jerusalem.”

It was hours after Alisa’s death, in his hotel room, that the phone rang, and Flatow first heard the voice of President Bill Clinton. “ ‘You are a brave man,’ ” he told me. I said, ‘Mr. President, you would do anything for your daughter, wouldn’t you?’ ‘Absolutely,’ he answered. I said, ‘Just because Alisa is no longer with me, I’m not going to stop being her father.’ ” Before signing off, Clinton said, “God bless you.” It was not to be the last conversation between the two men.

‘Track down and punish those responsible’

Soon afterwards, Flatow began traveling the country speaking not only about not only his daughter’s death at the hands of terrorists, but about the never-ending Israeli-Palestinian peace process. How, he writes, “could there be a process without a dedication on both sides to peace? And where was that dedication when the Palestinian leaders could not, or would not, keep their people from taking the lives of innocent Jews?”

But, he continues, he was driven by the need for his government “to track down and punish the people responsible for Alisa’s murder. The process was deeply frustrating … The two groups that vied with each other for bragging rights about killing Jews were Islamic Jihad and Hamas; almost immediately after the attack that killed Alisa, Islamic Jihad sent out a fax taking credit for it. Taking credit for killing my daughter. You can imagine how I felt.”

‘The law was the way’

Meeting with the president, Flatow said he urged him to “pressure Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to crack down on Islamic Jihad and Hamas. Clinton nodded, agreeing that Arafat would have to play a crucial part in stopping acts of terrorism. But as much as the president seemed to understand what I was saying, I was left with a hollow feeling. What would really be done?”

Clinton, it would turn out, was in the midst of working behind the scenes to try to keep everyone happy to ensure the success of his Oslo Peace Accords. Including Iran, which around this time, Flatow learned, was promoting the allure of martyrdom and suicide-bombing.

Their goal was the passage of the Flatow Amendment, designed to empower terrorism victims and their families to hold responsible parties responsible.

Flatow refused to accept that any would-be martyr could take his child’s life and get away with it. So he teamed up with attorney Steven Perles, an expert in international law, who would be his partner for the 10 years it would take to reach the end of a harrowing and all-consuming legal battle. (Note: The Flatow story is the subject of a motion picture now in development).

“It amazes me how much of what we could call Torah law has carried over into civil law,” writes Flatow. But the provision of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” was meant to insist on “compensation—not vengeance, but justice.”

And it was justice that Flatow was focused on. “That was what I wanted for my daughter. And the law was the way.”

In the end of the day, that is what he got. But it wouldn’t be easy.

For starters, Flatow writes, the law Clinton had just signed covering compensation for families of terror victims, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), in order to squeeze through administrative hoops, had been rendered somewhat toothless.

“The AEDPA needed to be strengthened, sure, but only Congress could do that—and only if we lobbied these powerful guys, hard. That realization was my welcome to Washington.”

For six months, Flatow logged thousands of miles on train, plane and automobile from his New Jersey home as he and Perles crisscrossed Capitol Hill. Their goal was the passage of the Flatow Amendment, designed to empower terrorism victims and their families to hold responsible parties responsible.

“I was the leverage. Who wants to turn away a grieving father?” Eventually, they pulled together a bipartisan coalition, including Sens. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.) and Connie Mack (R-Fla.), and Reps. Jim Saxton (R-N.J.), Henry Hyde (R-Ala.) and Ben Gilman (R-N.Y.), whose support made the amendment’s passage a reality, Flatow maintains. “Perles was delighted and said to me, ‘I don’t know how that happened. ‘Alisa, Steve, it was Alisa,’ I replied.”

Testifying on Capitol Hill before the Foreign Relations Committee—with a $400 million gift to the P.A. on the table—Flatow “let them have it, saying. ‘I had assumed my daughter’s killers would be hunted down, but I was beginning to wonder just how much my own government was committed to that. Why hadn’t the U.S. pressured the Palestinian Authority to find those suspected of terrorism and turn them over to us?’ I said: ‘I must then ask what kind of partnership is the United States going to have with the Palestinian Authority. Will it continue to turn a blind eye to this cancer?’ ” The upshot of the hearing: the money eventually did wind up fattening the P.A. coffers.

And, as yet another piece of legislation was introduced in 1999, the Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act, designed to allow victims and their families to attach terror-sponsoring governments’ assets, it included an “escape clause,” writes Flatow. It allows a president to waive the law if in his judgment a situation constitutes a threat to national security.

It was, he says, an escape clause “which Bill Clinton had happily escaped through.”

‘Roadblock after frustration after setback’

“The Iranian government was our enemy. They had financed the bombing that killed my daughter. It was deeply frustrating to have to tangle with my own government in order to take on Iran, as much as I understood the reasons, the bigger picture … . But if I had to tangle with the U.S. government to do what needed doing, so be it.”

As he tells it, Flatow “encountered roadblock after frustration after setback.” At a hearing on the new bill, he told the committee: “Am I frustrated and discouraged? Absolutely. Am I going to quit? No, Mr. Chairman, I am not. A father’s responsibility to his child does not end with her murder.”

“I tried to hit one out of the ballpark using the bat and ball provided by Congress.”

Support then came from an unexpected source. Hillary Clinton announced her bid for a New York Senate seat and was desperate for the Jewish vote, notably at risk after the kiss heard around the world that she’d planted on Suha Arafat’s cheeks.

So Flatow stood up at Clinton’s meetup with the Orthodox community and asked her: “Do you support the administration’s efforts that are blocking victims of terror from obtaining Iranian assets in this country?”

“She was very direct … She looked at me when she gave her answer … ‘No, I do not.” Contradicting her husband’s policies? It was an encouraging moment for Flatow.

And, despite repeated setbacks, there was fresh hope in Congress. Rather than reintroducing the weakened bill as a standalone the president could easily veto, supporters attached it another bill, a protection against human trafficking. “It was akin to a bill calling for people to be kind to their grandmothers—nobody was opposed to it, at least not publicly,” he writes. The bill passed the Senate 95-0, and the House vote was nearly unanimous.

When they finally got their day in court, the Flatow family was awarded $26 million.

After the legal costs, Flatow’s share went to support causes that Alisa herself would have applauded. “What had struck me about Alisa and her trips to Israel was that whenever she returned, she came back not simply as a ‘better Jew’ but as a better person. There’s something intangible in the Israel experience that changes a student.”

One investment: The Alisa Flatow Scholarship Fund, enabling young adults to study in Israel.

“I wonder, in telling this story, if I sometimes sound simply like a man who suffered a terrible misfortune and just won’t stop talking about it,” writes Flatow. “But what I hope I’ve made clear is that all of this is bigger than me—and as much as it hurts a father to say so, it’s bigger than Alisa, too.”

(Indeed, Flatow has also helped the families of other victims achieve judgements against Iran.)

“My efforts, which for a time had seemed so futile, turned out to be worthwhile,” he writes. “I had, at long last, struck something of a blow for my daughter. It wasn’t everything I’d wanted, but, in the end, I saw the wisdom in doing so.”

During their last phone conversation with their daughter, Flatow and his wife asked where she’d be traveling and with whom, the usual parental interrogation of a long-distance child. “Roz turned to me and she said, ‘You didn’t get the name of the hotel where she’ll be staying. What if something happens?’ For some reason I said, ‘Don’t worry. If something happens, we’ll know about it.’ Well, I was not wrong about that.”

Twenty-three years later, the Flatows’ four surviving children in the United States and Israel are thriving and there are grandchildren galore—four of whom are named after the aunt they would never meet.

But just because he finally had his day in court and extracted as much justice as could be expected, Flatow now has enough insider insights to keep him fighting a disturbing status quo.

“The Obama administration’s removal of sanctions in exchange for the ‘nuclear deal’ in 2015, and the return to Iran of billions of dollars in frozen assets … has given Tehran the ability to increase weapons support for Hezbollah and financial aid to Hamas and Islamic Jihad,” he writes at book’s end. “Few can argue that this is a good occurrence.”

And he’s come through it all with a strengthened belief: “Jews, whether in Israel or America, we have the right—not only the right, but the duty—to stand up for ourselves, because if we do not, then who will?”

“As for me, I tried to hit one out of the ballpark using the bat and ball provided by Congress. I never expected that the Clinton administration would put its full weight against me and other terror victims. When it did happen, I didn’t scream or shout in rage. Instead, I let my lawyers speak for me in court, and I took my case to the public. In the end, it may not have been a grand slam, but I believe I did a decent job for a father from New Jersey standing up for his daughter.”